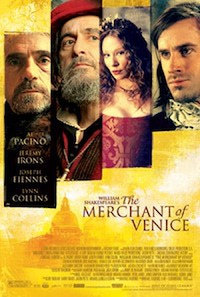

And I beseech you,

Wrest once the law to your authority:

To do a great right, do a little wrong,

And curb this cruel devil of his will.The Merchant of Venice: Act 4, Scene I

I think it is rather as though Jack Straw has been seduced by Bassanio’s arguments. For, to do a great right by the gay community, he has this week chosen to do what he must regard as no more than a little wrong to the right to freedom of expression.

The UK already has legislation on incitement to racial hatred (as does Ireland, also here), it has recently extended that legislation to cover incitement to religious hatred, and just this week Straw announced the UK government’s intention to extend it further to cover incitement to hatred based on sexual orientation. The Ministry of Justice press release says:

Justice Secretary Jack Straw said:

“It is a measure of how far we have come as a society in the last 10 years that we are now appalled by hatred and invective directed at people on the basis of their sexuality. It is time for the law to recognise this.”

Equalities Secretary Harriet Harman said,

“Fighting hatred, prejudice and discrimination will be at the heart of everything this government does.”

The new law would not prohibit criticism of gay, lesbian and bisexual people, but it would protect them from incitement to hatred against them because of their sexual orientation.

There has been quite a bit in the news about this (BBC | The Guardian | International Herald Tribune | The Daily Telegraph | Sky | The Times | Yahoo! news | politicis.co.uk). Predictably, Stonewall has welcomed this (Ben Summerskill, Stonewall Chief Executive, said: ‘We’re delighted. …’), as has the gay blogosphere (Adriano | Gay Republic | Gay News Blog | Pink News | Phlamer | Swinging Both Ways | Towleroad) and others (eg Coventry Green Party | Real Labour Blogger), and it has provoked the predictable range of responses (Anglican Mainstream | BNP | Catholic Action UK | Muslims Today | Smug Board). My favourite comments are Unspeak and Comment is Free, (thoughtful discussion by Steven Poole) and Harry’s Place (very balanced analysis).

Nor is the UK alone in heading in this direction. We have already seen some EU proposals; and there are similar Council of Europe developments. Moreover, Jack Straw is right, society has come a long way over the last 10 or so years. But he is now putting that gain in peril. One of the many reasons why so much progress has been made over the last ten years is because members of the gay, lesbian, bisexual and transgender communities have been able to argue their case. It is an example of free speech in action. Indeed, it is an excellent example of how majority opinion can be changed by good arguments, well expressed. But it is an even better example of why majorities should never legislate for their pieties and against their opponents. If the old consensus had legislated against pro-gay arguments, we could never have matured as we have. They should continue to argue their case as forcefully as they already have. If they have a problem with what the BNP says, don’t ban them; persuade me that the BNP are wrong. If they have a problem with a rap artist’s homophobia, don’t ban him; persuade Tower or iTunes not to distribute it; persuade me not to buy his cds or download his songs. Don’t ban; persuade.

However, I am not at all sure whether this legislation would be contrary to Article 10 of the European Convention on Human Rights, which reads:

1. Everyone has the right to freedom of expression. This right shall include freedom to hold opinions and to receive and impart information and ideas without interference by public authority and regardless of frontiers. This Article shall not prevent States from requiring the licensing of broadcasting, television or cinema enterprises.

2. The exercise of these freedoms, since it carries with it duties and responsibilities, may be subject to such formalities, conditions, restrictions or penalties as are prescribed by law and are necessary in a democratic society, in the interests of national security, territorial integrity or public safety, for the prevention of disorder or crime, for the protection of health or morals, for the protection of the reputation or rights of others, for preventing the disclosure of information received in confidence, or for maintaining the authority and impartiality of the judiciary.

Now, let us assume that the proposed legislation does indeed infringe the Article 10(1) right to freedom of expression. The question will be whether it is saved by Article 10(2). If indeed there is legislation, then it is “prescribed by law”; and I am sure that the UK would argue that it is justifiable on the basis of the need to prevent “disorder or crime” and “the protection of the… rights of” gay people; it will then have to demonstrate that it was “necessary” to meet those needs. And the European Court of Human Rights has held that restrictions will be necessary only if they are proportionate to the legitimate aim being pursued. In the leading case of Jersild v Denmark 15890/89 [1994] ECHR 33 (23 September 1994) (also here) the Court struck down a journalist’s conviction for having aided and abetted the dissemination of racist remarks on the grounds that it violated his right to freedom of expression. But it was close run thing, turning on the fact the journalist was not a racist but merely reporting on racist organisations in Denmark:

30. The Court would emphasise at the outset that it is particularly conscious of the vital importance of combating racial discrimination in all its forms and manifestations. …

31. A significant feature of the present case is that the applicant did not make the objectionable statements himself but assisted in their dissemination in his capacity of television journalist responsible for a news programme of Danmarks Radio …

The Court reiterates that freedom of expression constitutes one of the essential foundations of a democratic society and that the safeguards to be afforded to the press are of particular importance. Whilst the press must not overstep the bounds set, inter alia, in the interest of “the protection of the reputation or rights of others”, it is nevertheless incumbent on it to impart information and ideas of public interest. Not only does the press have the task of imparting such information and ideas: the public also has a right to receive them. Were it otherwise, the press would be unable to play its vital role of “public watchdog”. Although formulated primarily with regard to the print media, these principles doubtless apply also to the audiovisual media.

In considering the “duties and responsibilities” of a journalist, the potential impact of the medium concerned is an important factor and it is commonly acknowledged that the audiovisual media have often a much more immediate and powerful effect than the print media. The audiovisual media have means of conveying through images meanings which the print media are not able to impart. …

The Court will look at the interference complained of in the light of the case as a whole and determine whether the reasons adduced by the national authorities to justify it are relevant and sufficient and whether the means employed were proportionate to the legitimate aim pursued. …

35. News reporting based on interviews, whether edited or not, constitutes one of the most important means whereby the press is able to play its vital role of “public watchdog”. The punishment of a journalist for assisting in the dissemination of statements made by another person in an interview would seriously hamper the contribution of the press to discussion of matters of public interest and should not be envisaged unless there are particularly strong reasons for doing so. …

36. It is moreover undisputed that the purpose of the applicant in compiling the broadcast in question was not racist. Although he relied on this in the domestic proceedings, it does not appear from the reasoning in the relevant judgments that they took such a factor into account.

37. Having regard to the foregoing, the reasons adduced in support of the applicant’s conviction and sentence were not sufficient to establish convincingly that the interference thereby occasioned with the enjoyment of his right to freedom of expression was “necessary in a democratic society”; in particular the means employed were disproportionate to the aim of protecting “the reputation or rights of others”. Accordingly the measures gave rise to a breach of Article 10 of the Convention.

Since the case turned on the rights of the reporter, it doesn’t strike me as strong authority for the compatibility of the racist speech itself. No doubt, if Straw enacts his proposed legislation, a conviction under it will be challenged on Article 10 grounds, and we will have our answers. But I would hope that it would not come to this. The right to freedom of expression should not be curtailed in an understandable but misguided exercise of raw political power. It is a great right, and should be exercised and celebrated as such.

Apologies to those who saw an early version of this message, where the original image first took ages to load and then died completely. If it’s come back to life, it’s here. The replacement also proved a problem, and if it’s come back to life, it’s here. With a bit of luck, the third effort above will prove less of a problem (though it’s a less pretty poster – oh, well).