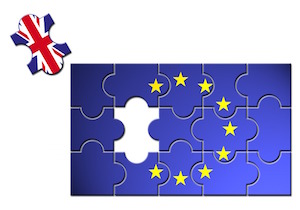

I still can’t believe the news about Brexit, and I suspect the same is true of many on both sides of the issue. Since then, there has been much talk about Article 50, and much speculation about the possibility of a second referendum to undo the first. In this brief post, I want to put those two issues together. First, Article 50 is an article of the Treaty on European Union inserted by the Treaty of Lisbon. It is the mechanism by which a Member State may leave the EU. It provides in full as follows (with added links):

I still can’t believe the news about Brexit, and I suspect the same is true of many on both sides of the issue. Since then, there has been much talk about Article 50, and much speculation about the possibility of a second referendum to undo the first. In this brief post, I want to put those two issues together. First, Article 50 is an article of the Treaty on European Union inserted by the Treaty of Lisbon. It is the mechanism by which a Member State may leave the EU. It provides in full as follows (with added links):

- Any Member State may decide to withdraw from the Union in accordance with its own constitutional requirements.

- A Member State which decides to withdraw shall notify the European Council of its intention. In the light of the guidelines provided by the European Council, the Union shall negotiate and conclude an agreement with that State, setting out the arrangements for its withdrawal, taking account of the framework for its future relationship with the Union. That agreement shall be negotiated in accordance with Article 218(3) of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union. It shall be concluded on behalf of the Union by the Council, acting by a qualified majority, after obtaining the consent of the European Parliament.

- The Treaties shall cease to apply to the State in question from the date of entry into force of the withdrawal agreement or, failing that, two years after the notification referred to in paragraph 2, unless the European Council, in agreement with the Member State concerned, unanimously decides to extend this period.

- For the purposes of paragraphs 2 and 3, the member of the European Council or of the Council representing the withdrawing Member State shall not participate in the discussions of the European Council or Council or in decisions concerning it.

A qualified majority shall be defined in accordance with Article 238(3)(b) of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union. - If a State which has withdrawn from the Union asks to rejoin, its request shall be subject to the procedure referred to in Article 49 [of the Treaty on European Union].

Let us assume that, following the Brexit referendum vote and pursuant to the UK’s own constitutional requirements, the procedure in this Article is triggered, and agreement is reached between the UK and EU on the terms of a withdrawal agreement.

[Revised and updated]: An excellent guide to the process is provided in the House of Lords’ European Committee Paper on The process of withdrawing from the European Union (11th Report of Session 2015–16; HL Paper 138; html | pdf); a clear practical summary of the process is helpfully set out by the BBC EU spells out procedure for UK to leave; and Duncan French provides very clear analysis of the legal implications of the UK’s renegotiation and withdrawal. As to the necessary UK Parliamentary procedures, see Nick Barber, Tom Hickman & Jeff King on Pulling the Article 50 ‘Trigger’: Parliament’s Indispensable Role and the replies by Carl Gardner’s Article 50, and UK constitutional law and Kenneth Armstrong Push Me, Pull You: Whose Hand on the Article 50 Trigger?.

My question is, could the UK government put that withdrawal agreement to a further referendum, asking in effect if the UK should ratify it and bring it into force? And if it does, is there any route by which a vote to reject the withdrawal agreement and to remain in the EU could be given effect? The terms of withdrawal would be clear, and the choice facing the voters would be more realistic and more focussed than in last week’s referendum. I will leave the politics of this to others, but I will raise here two of the (doubtless many, many) legal issues which arise.

The first issue is whether this is possible from the perspective of the UK’s constitutional requirements. I don’t see why not, but I welcome comments as to whether this is so. As with the current referendum, by virtue of the doctrine of Parliament Sovereignty, it would only be a pre-legislative and non-binding advisory referendum, but Parliament would be very slow indeed to decline to act accordingly.

The second issue is whether this is possible from the perspective of the Article 50 TEU (above). Here, things are a little more opaque. On a literal interpretation of the Article, it does not seem to provide for the suspension of the withdrawal process, but the CJEU has never tied itself to an exclusively literal approach to the European Treaties. Instead, as former CJEU Advocate General and retired Irish Supreme Court judge, Nial Fennelly, explains:

The characteristic element in the Court’s interpretative method is … [the] “teleological” approach, … that it is necessary to consider “the spirit, the general scheme and the wording,” supplemented later by consideration of “the system and objectives of the Treaty.” In more recent years, the idea of “context” has been added, and the prevailing wording, varying minimally from case to case, has been that it is necessary when interpreting a provision of Community law to consider “not only its wording, but also the context in which it occurs and the objects of the rules of which it is a part.”

I suspect that the CJEU would, on this basis, be able to find that the Article 50 process could be suspended or abandoned, but I would not wish to predict whether it would do so. It is a Court often noted for its realpolitik and pragmatism, but there are limits to how far it can or will go to accommodate political agreements. It might perhaps be asked for an advisory opinion on the issue. If the CJEU finds that suspension or abandonment of the Article 50 process is possible, if a second Brexit referendum were to be in favour of remain, if Parliament therefore indicated its intention not to ratify the withdrawal agreement, if the UK government consequently sought the suspension or abandonment of the Article 50 process, and if the other Member States – via the European Council – agreed, then the Article 50 process could be suspended or abandoned.

If suspension or abandonment is not possible, then the issue will turn on Article 50, paragraph 2 (above), which provides that the EU Treaties cease to apply to the departing Member State in two circumstances: either on the entry into force of the withdrawal agreement, or two years after Member State notifies the EU that it wished to begin negotiations for withdrawal “unless the European Council, in agreement with the Member State concerned, unanimously decides to extend this period”. If a second Brexit referendum were to be in favour of remain, and Parliament therefore indicates its intention not to ratify the withdrawal agreement, the first alternative in Article 50 paragraph 2 is satisfied, and the withdrawal agreement would not come into force on that ground.

More complications arise under the second alternative, by which the withdrawal seems automatic after two years “unless the European Council, in agreement with the Member State concerned, unanimously decides to extend this period”. So, the question is: could some form of words be agreed “to extend this period” indefinitely? And even if so, would the CJEU uphold it? Again, I would not wish to predict whether it would, and it might again be asked for an advisory opinion on the issue.

Rather less susceptible to a successful challenge would be a form words that clove more closely to Article 50 and did not expressly say that it would extend the period “indefinitely”. Instead, it might provide that the period would be extended until a withdrawal agreement enters into force. That could – and, in practice, probably would – amount to an indefinite extension, but it would be much closer to the spirit of Article 50, and well within the linguistic flexibility that has been shown in Treaty negotiations in the past. As before, I would not wish to predict whether the CJEU would uphold such a formulation, and an agreement to this effect might form the basis on which it could be asked for an advisory opinion on the issue. If the CJEU approves a form of words by which automatic withdrawal would be postponed until a withdrawal agreement enters into force, if a second Brexit referendum were to be in favour of remain, if Parliament therefore indicated its intention not to ratify the withdrawal agreement, if the UK government consequently sought the postponement of automatic withdrawal until a withdrawal agreement enters into force, and if the other Member States – via the European Council – agreed, then the second alternative in Article 50 paragraph 2 is satisfied, and the withdrawal agreement would not come into force on that ground.

I am even less clear on this EU issue than I am on the UK constitutional issue above, and I equally welcome comments as to whether this is legally possible. I leave the question of whether this is likely to the politicians.

Let us therefore assume that the UK would negotiate a withdrawal agreement pursuant to Article 50, and put it to the people in a referendum. Let us further assume that the result in that referendum is in favour of remain, such that the withdrawal agreement is rejected, and Parliament therefore declines to ratify that agreement and bring into force. In such circumstances, my question is this: could the UK rely on an agreement with the other Member States – via the European Council – either that the Article 50 process would be suspended or abandoned, or that any automatic withdrawal would be postponed until a withdrawal agreement enters into force? In either case, the result would be that the Article 50 process would have provided route, via a second Brexit referendum, to ensuring that the UK would not have left the EU. Time may well tell. Meanwhile, answers on a postcard …

5 Reply to “There may be an Article 50 route to a second Brexit referendum and the UK remaining in the EU”