Banks are more often cast in the role of Scrooge than Santa; and, even when they start out in the latter role, they end up in the former.

Banks are more often cast in the role of Scrooge than Santa; and, even when they start out in the latter role, they end up in the former.

For example, where over-active ATMs played Santa and permitted withdrawals of amounts greater than available funds or credit, the bank quickly became Scrooge, insisting that all money withdrawn by customers in excess of their balances will have to be repaid. Unlike in monopoly, you cannot retain the proceeds of a bank error in your favour. It’s not a gift either from God or from the bank. As I have explained many times on this blog, this is a mistaken payment, and the recipient must return it, unless there is a defence. And, if it is not returned, it could constitute theft.

Just before Christmas, Santander bank found itself first as Santa and then as Scrooge:

Bank accidentally deposits $176 million into people’s accounts on Christmas Day

Thousands of people received a surprise gift on Christmas Day this year when European bank Santander accidentally deposited £130 million ($176 million) across 75,000 transactions.

The mistake happened when payments from 2,000 business accounts in the U.K. were processed twice, meaning some employees saw their wages double, while suppliers also got more than they were expecting. The bank said the duplicate payments were caused by a “scheduling issue” that has now been rectified. It is now trying to recuperate the mistaken payments, many of which have gone into bank accounts operated by rival banks. …

More: BBC | CNN | New York Post | New York Times | The Guardian | The Verge

Santander have not had the best of luck with their computer systems: they suffered outages affecting customers in May, August and November 2021; and they were named the UK’s worst bank for online banking services last year.

As a New Zealand businessman recently discovered, it’s very likely that Santander will recover these double payments:

‘Lame excuse’ fails for man who tried to keep $50k mistakenly deposited into bank account

A businessman was ordered to pay back more than $50,000 mistakenly deposited into his bank account after a judge dismissed his “lame excuse” for trying to keep the cash. … [The payor had] mistakenly selected the wrong payee. … [The judge held:]

I reject the defendant’s evidence that on receipt of the funds he considered this was a voluntary payment by the plaintiff to have him change the name of ITS. I find that Mr Mayer acted in bad faith by not immediately refunding the money to the plaintiff. …

If it had been a voluntary payment, then it would not have been mistaken, and the recipient could have retained it. But if, as here, it was not voluntary, and if it was mistaken, then the recipient has to return it. Apart from voluntary enrichment, two other – often more plausible – defences are change of position and discharge for value; and, if one is established, the bank remains as a gift-giving Santa, albeit an unwilling one. This is graphically illustrated by In re Citibank (SDNY; 16 February 2021; Furman J) (pdf | Justia) (already briefly mentioned on this blog). Revlon was a customer of Citibank, and had borrowed from other lenders. Revlon authorized Citibank to make interest payments to the lenders totaling US$7.8 million. Instead, Citibank mistakenly paid the loans in full, in the amount of c.$894 million. When they discovered their mistake, Citibank sought to get the money back from the lenders; some complied and repaid c.$393 million. But 10 lenders simply refused to return the remaining c.$500m.

If it had been a voluntary payment, then it would not have been mistaken, and the recipient could have retained it. But if, as here, it was not voluntary, and if it was mistaken, then the recipient has to return it. Apart from voluntary enrichment, two other – often more plausible – defences are change of position and discharge for value; and, if one is established, the bank remains as a gift-giving Santa, albeit an unwilling one. This is graphically illustrated by In re Citibank (SDNY; 16 February 2021; Furman J) (pdf | Justia) (already briefly mentioned on this blog). Revlon was a customer of Citibank, and had borrowed from other lenders. Revlon authorized Citibank to make interest payments to the lenders totaling US$7.8 million. Instead, Citibank mistakenly paid the loans in full, in the amount of c.$894 million. When they discovered their mistake, Citibank sought to get the money back from the lenders; some complied and repaid c.$393 million. But 10 lenders simply refused to return the remaining c.$500m.

More: Ars Technica | Bloomberg here and here | CNBC | CNN here and here | Financial Times here and here | JD Supra here, here, here and here | National Law Review | New York Times | Reuters here and here | Wall Street Journal.

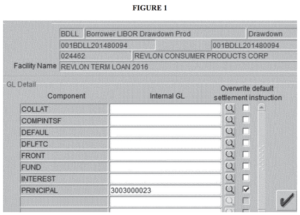

Furman J held that Citibank had made a mistake, by checking only one of the three necessary boxes on the computer interface (pictured left) to indicate that the payment was only interest and not principal. So a terrible user interface meant that Citibank made a mistaken payment of nearly $900m, of which just over $500m was still outstanding. However, although Citibank had a prima facie cause of action, the defendants were able to rely on the defence of “discharge for value” (following Banque Worms v BankAmerica International 928 F2d 538 (2d Cir, 1991); Andrew Kull “Defenses to Restitution: The Bona Fide Creditor” 81 Boston University Law Review 919 (2001) (Hein); Andrew Kull “Restitution and Final Payment” 83 Chicago-Kent Law Review 677 (2008)): because they lenders had discharged Revlon’s loans, they had provided value for the payments, and thus could keep them (Elisabeth de Fontenay “The $900 Million Mistake: In re Citibank August 11, 2020 Wire Transfers (S.D.N.Y. Feb. 16, 2021)” (2021) 16(3) Capital Markets Law Journal 307 (SSRN); Eric L Talley “Discharging the Discharge for Value Defense” (2021) 18(1) New York University Journal of Law and Business (forthcoming; SSRN; pdf via ecgi; Maytal Gilboa & Yotam Kaplan “The Costs of Mistakes” Columbia Law Review Forum (forthcoming) (SSRN) (arguing that Citibank should have been decided differently, and should be reversed on appeal)). The decision is under appeal (Bloomberg | Reuters) so there will be more about it on this blog in due course (update: blogged here).

Furman J held that Citibank had made a mistake, by checking only one of the three necessary boxes on the computer interface (pictured left) to indicate that the payment was only interest and not principal. So a terrible user interface meant that Citibank made a mistaken payment of nearly $900m, of which just over $500m was still outstanding. However, although Citibank had a prima facie cause of action, the defendants were able to rely on the defence of “discharge for value” (following Banque Worms v BankAmerica International 928 F2d 538 (2d Cir, 1991); Andrew Kull “Defenses to Restitution: The Bona Fide Creditor” 81 Boston University Law Review 919 (2001) (Hein); Andrew Kull “Restitution and Final Payment” 83 Chicago-Kent Law Review 677 (2008)): because they lenders had discharged Revlon’s loans, they had provided value for the payments, and thus could keep them (Elisabeth de Fontenay “The $900 Million Mistake: In re Citibank August 11, 2020 Wire Transfers (S.D.N.Y. Feb. 16, 2021)” (2021) 16(3) Capital Markets Law Journal 307 (SSRN); Eric L Talley “Discharging the Discharge for Value Defense” (2021) 18(1) New York University Journal of Law and Business (forthcoming; SSRN; pdf via ecgi; Maytal Gilboa & Yotam Kaplan “The Costs of Mistakes” Columbia Law Review Forum (forthcoming) (SSRN) (arguing that Citibank should have been decided differently, and should be reversed on appeal)). The decision is under appeal (Bloomberg | Reuters) so there will be more about it on this blog in due course (update: blogged here).

The defence would also seem applicable to mistaken payment claims in the common law world outside the US (Burgess Salmon; Stephenson Harwood). In general, a defendant, who has given value to a third party in exchange for the enrichment which the plaintiff now seeks to recover, may be able to rely on the defence of bona fide purchase. “Such a defence is available … to defeat … a personal claim in unjust enrichment” (JSC BTA Bank v Ablyazov [2018] EWCA Civ 1176 (22 May 2018) [60] (Leggatt LJ; Gloster VP and Coulson LJ concurring); this must have overtaken the contrary view in Armstrong DLW GmbH v Winnington Networks Ltd [2013] Ch 156, [2012] EWHC 10 (Ch) (11 January 2012) [105] (DHCJ Stephen Morris QC)). In Barclays Bank Limited v Simms [1980] QB 679, 695, Goff J held that a claim for restitution on the grounds of mistake would fail, inter alia, if

the payment is made for good consideration, in particular if the money is paid to discharge and does discharge a debt owed to the payee (or a principal on whose behalf he is authorised to receive the payment) by the payer or by a third party by whom he is authorised to discharge the debt …

In Dextra Bank & Trust Company Ltd v Bank of Jamaica [2001] UKPC 50 (26 November 2001), Beckford presented Dextra’s cheque for $2,999,000 to the Bank of Jamaica [BOJ], ostensibly to permit Beckford to purchase foreign currency on behalf of Dextra. The BOJ paid Beckford, who were fraudsters, and Dextra never received the foreign currency. Their claim to recover the value of the cheque from the BOJ failed for various reasons. One was that, having paid Beckford, the BOJ were bona fide purchasers of Dextra’s cheque; Lords Goff and Bingham held:

47. … It is commonly accepted that the defence of bona fide purchaser is only available to a third party, which includes an indirect recipient, ie a person who received the benefit from somebody other than the plaintiff or his authorised agent. Here the BOJ received the cheque from Beckford who was acting without authority from Dextra in selling the cheque to the BOJ, so that the BOJ can properly be described as an indirect recipient; and the BOJ … paid for the cheque in accordance with the directions of Beckford. In so doing, the … BOJ acted in good faith. In agreement with the majority of the Court of Appeal, their Lordships can see no reason why the BOJ should not be entitled to invoke the defence of bona fide purchase in answer to Dextra’s restitutionary claim ….

So, in Bank of Cyprus UK Ltd v Menelaou [2015] UKSC 66, [2015] UKSC 66 (4 November 2015), had the appellant “been a bona fide purchaser for full value, it may very well have been impossible to characterise her enrichment as unjust, especially if she had no notice of the Bank’s rights” ([70] (Lord Neuberger; Lords Kerr and Wilson concurring); Lowick Rose LLP v Swynson Ltd [2018] AC 313, [2017] UKSC 32 (11 April 2017) [29] (Lord Sumption; Lords Neuberger, Clarke and Hodge concurring); XL Insurance Company SE v IPORS Underwriting Ltd [2021] EWHC 474 (Comm) (04 March 2021) [76] (Cockerill J)). However, the appellant in Menelaou “was not a bona fide purchaser for value without notice” ([2015] UKSC 66 [36] (Lord Clarke)).

In Nelson v Larholt [1948] 1 KB 339, a defendant paid a third party on foot of a cheque drawn on the plaintiff; and Denning J held that the defendant, despite having given value (and thereby purchased), had not made reasonable enquires and thus had notice of the plaintiff’s claim. In Lipkin Gorman v Karpnale [1991] 2 AC 548, [1988] UKHL 12 (06 June 1991), a partner in a firm of solicitors had gambled the firm’s money at the defendant club, and in the firm’s action to recover the money, the club sought to argue that since it had given value to the solicitor, it could rely on the defence of bona fide purchase; but the House of Lords held that the nullity of the gaming contract between the club and the partner meant that the club were not purchasers for value. Again, in Polly Peck v Nadir (No 2) [1992] 4 All ER 769 (CA) 781-782, Scott LJ held that a bank receiving sterling and exchanging it for foreign currency receives the sterling for its own use and benefit, but the bank’s bona fide purchase of the foreign currency without notice of the plaintiff’s claim afforded the bank a defence (see, generally, Paul Key “Bona Fide Purchase as a Defence in the Law of Restitution” [1994] Lloyd’s Maritime & Commercial Law Quarterly 421; Kit Barker “Bona Fide Purchase as a Defence to Unjust Enrichment Claims: A Concise Restatement” (1999) 7 Restitution Law Review 75 (SSRN); Sonja Meier “Bona Fide Purchase as a Defence in Unjust Enrichment” in Andrew Dyson, James Goudkamp & Frederick Wilmot-Smith (eds) Defences in Unjust Enrichment (Hart, 2016) Chapter 11; cf Struan Scott”Mistaken Bank Payments: Commercial Certainty Counts” (2006) 11 Otago Law Review 209, [2006] OtaLawRw 4 (arguing that the reasoning in Barclays Bank v Simms is too restitutionary, and that, where a bank overlooks its customer’s “stop-payment” instruction and mistakenly honours the earlier payment instruction, the payee should have a “good consideration” defence on the ground that he or she gave consideration for the receipt, by accepting the money in satisfaction of the debt owed by the customer)).

Lloyds Bank Plc v Independent Insurance Co Ltd [2000] QB 110, [1998] EWCA Civ 1853 (26 November 1998) is very similar in structure to Citibank, though the value of the claim is far less. WF Insurance Services, instructed their bank, Lloyds, to pay £107,387.90 to Independent Insurance. Lloyds, mistakenly believing that a recent deposit into WF’s account had cleared, made the payment, which discharged WF’s debt to Independent. The Court of Appeal dismissed Lloyds’ claim for restitution of their mistaken payment. Peter Gibson LJ applied Simms, and held that Independent was entitled to receive the sum paid to it in discharge of the debt owed to it by WF. Hence, in Standard Bank London Ltd. v Canara Bank [2002] EWHC 1032 (Comm) (22 May 2002) [99] Moore-Bick J held that, in order for the payee to have given good consideration “it is necessary that the payment operate in discharge of the debt and for that to occur the payment must have been made and received with the necessary authority”. On the other hand, in cf Jones v Churcher [2009] 2 Lloyds Rep 94, [2009] EWHC 722 (QB) (18 March 2009) HHJ Havelock-Allan QC held the bank did not give good consideration to third parties for the receipt).

Moreover, by way of an interesting aside, in Lloyds Bank Plc v Independent Insurance Co Ltd, Peter Gibson LJ observed that

… the conclusion that a payment made under a mistake but in discharge of a debt is irrecoverable is consistent with the American Restatement of the Law of Restitution, … In section 33 it is stated that the holder of a cheque or other bill of exchange who, having paid value in good faith therefor, receives payment from the drawee without reason to know that the drawee is mistaken is under no duty of restitution to him although the drawee pays because of a mistaken belief that he has sufficient funds of the drawer. The commentary states that the payee is entitled to retain the money which he has received as a bona fide purchaser, and the illustrations given by way of typical cases include the payment by a bank of a cheque drawn on it by a customer who has insufficient funds to cover the cheque, the payment going to discharge a mortgage debt.

In Banque Worms, the Second Circuit Court of Appeals held that New York had adopted the Restatement‘s discharge for value rule; and, in Citibank, Furman J applied to provide the payees with a defence.

Finally, the duty to make restitution of a bank overpayment does not always run smoothly, as is neatly illustrated to great comedic effect in the Frasier episode “Roe to Perdition” (series 10, episode 18). There are two main storylines in the episode (spoiler alert: the episode was first aired on 18 March 2003; so if you haven’t seen it by now and you don’t want spoilers, tough – like, where have you been all this time?). One, reflected in the episode title, relates to Frasier and Niles trading in Russian mafia beluga caviar. The other involves an overactive ATM. Martin went to one for $20, and it gave him $60. He tells Frasier, Niles and Daphne that he’d “won 40 bucks”, but Daphne tells him it would be “bad karma” to keep it. Martin says that America is “a land built on the principle ‘finders keepers’,” but Daphne persuades (browbeats) him to return it.

Finally, the duty to make restitution of a bank overpayment does not always run smoothly, as is neatly illustrated to great comedic effect in the Frasier episode “Roe to Perdition” (series 10, episode 18). There are two main storylines in the episode (spoiler alert: the episode was first aired on 18 March 2003; so if you haven’t seen it by now and you don’t want spoilers, tough – like, where have you been all this time?). One, reflected in the episode title, relates to Frasier and Niles trading in Russian mafia beluga caviar. The other involves an overactive ATM. Martin went to one for $20, and it gave him $60. He tells Frasier, Niles and Daphne that he’d “won 40 bucks”, but Daphne tells him it would be “bad karma” to keep it. Martin says that America is “a land built on the principle ‘finders keepers’,” but Daphne persuades (browbeats) him to return it.

Sometimes, inexplicably, banks just don’t seem interested in taking the money bank (see, eg, National Bank of New Zealand v Waitaki International Processing [1999] 2 NZLR 211 (NZ CA)). So, when Marty rang the toll-free number on the ATM receipt to explain what happened, things don’t go smoothly. As Frasier hosts a caviar party, Martin is on the phone in the background trying to get the bank’s automatic voice system to process his call (his increasingly exasperated “CHECK-ING … CUS-TOM-ER—SER-VICE … PER-SON-AL” punctuate a conversation between Frasier and Niles about getting more mafia caviar to lubricate their way further up Seattle’s high society). Martin and Daphne therefore go to a branch of the bank (pictured right), where he grumpily fills out an ATM trouble report (Martin: “This is more trouble than it’s worth”; Daphne: “A little paperwork is a small price to pay for a clear conscience”). The bank misunderstands Martin’s issue. First, they think he’s seeking a refund, so they offer to pay him a further $40. Then, when he insists that he’s seeking to return it, they think he’s seeking to make a deposit. A few days later, at home, he receives a postcard from the bank, apologizing for the inconvenience, and informing him that they had credited his account with $80. A frustrated Martin returns to another branch of the bank, where his attempts to give slow and clear instructions to a teller lead a guard to conclude that he is a robber, so the guard holds him at gunpoint. Cut to a scene where the President of the bank reassures Martin that it is not their policy “to draw firearms on customers seeking to make a deposit” and offers to compensate him for his troubles in the amount of €10,000 “plus the $40 from our original mistake”, in exchange for him signing a non-disclosure agreement. Martin signs, and takes the money, and scarpers.

Whatever about Santander, Martin’s bank must be Citibank, because it is plainly Santa. No wonder Daphne seeks to open an account with them. Next time I’m in Seattle, so will I. Meantime, I think I’ll avoid Santander if I can.

In the first example above, Santander mistakenly processed credits twice, and the customers had to make restitution. It can happen the other way too, where the bank mistakenly processes a debit twice, and the recipient has to make restitution. A story on the RTÉ News website this morning illustrates the point:

From the BGE statement: