In an earlier post, I considered the settlement in Carey v Independent News & Media and the status of Bloomberg v ZXC [2022] AC 1158, [2022] UKSC 5 (16 February 2022) in Ireland. According to media reports this time last week, a case similar to Carey may very well be brewing:

In an earlier post, I considered the settlement in Carey v Independent News & Media and the status of Bloomberg v ZXC [2022] AC 1158, [2022] UKSC 5 (16 February 2022) in Ireland. According to media reports this time last week, a case similar to Carey may very well be brewing:

Sinn Féin TD takes breach of privacy action against Mediahuis and state (Barry Whyte, Business Post, 24 September 2023)

Martin Kenny also suing the gardaí and the state over a series of articles published last year which did not name him.Sinn Féin TD sues An Garda Síochána, Independent titles publisher and State (Colm Keena, Irish Times, 24 September 2023)

Martin Kenny is taking breach of privacy case arising from news report that did not name him or his party.

It seems that the articles in respect of which he is suing contain a quote from An Garda Síochána about an ongoing investigation into an alleged criminal offence, that they say that there was a connection to a politician who was a member of an unnamed party, and that they made it clear that there was no suggestion that this politician was being accused of any wrongdoing. As both sub-heads above make clear, these articles did not name Sinn Féin TD Martin Kenny (pictured, above right), but – like Carey – he must consider that he is sufficiently identifiable from the articles that his privacy has been invaded.

There are some interesting cases on when general references can sufficiently identify a plaintiff to support a claim of defamation at common law or for infringement of data protection rights pursuant to the GDPR.

There are some interesting cases on when general references can sufficiently identify a plaintiff to support a claim of defamation at common law or for infringement of data protection rights pursuant to the GDPR.

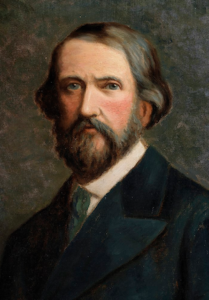

As to defamation, the leading case is the Irish case of Le Fanu v Malcolmson [1843-60] All ER Rep 152, (1848) 1 HLC 637, (1848) 9 ER 910, [1848] EngR 663 (27 June 1848) (pdf). Here, in The Warder newspaper published on on 1 June 1844 (sub req’d), under the headline “THE FACTORY QUESTION IN IRELAND”, Joseph Sheridan le Fanu (pictured left) wrote that “the abuses [in factories] in the county of Waterford exceed even those committed in England”, and he, as editor, published a letter that said that the “cruelties of the slave trade or the Bastille are not equal to those practised in some of the Irish factories”. A jury found that the article and letter referred to Joseph Malcolmson’s factory in Waterford. Lord Cottenham LC held:

If a party can publish a libel so framed as to describe individuals, though not naming them, and not specifically describing them by any express form of words, but still so describing them that it is known who they are, as the jurors have found it to be here, and if those who must be acquainted with the circumstances connected with the party described may also come to the same conclusion, and may have no doubt that the writer of the libel intended to mean those individuals, it would be opening a very wide door to defamation, if parties suffering all the inconvenience of being libelled were not permitted to have that protection which the law affords. If they are so described that they are known to all their neighbours as being the parties alluded to, and if they are able to prove to the satisfaction of a jury that the party writing the libel did intend to allude to them, it would be unfortunate to find the law in a state which would prevent the party being protected against such libels.

See also South Hetton Coal Co v North-Eastern News Association [1894] 1 QB 133; Jones v Halton [1909] 2 KB 444; Browne v DC Thomson & Co [1912] SC 359; Irish People’s Assurance Society v City of Dublin Assurance Company Ltd [1929] IR 25 (SC); Knuppfer v London Express Newspaper Ltd [1944] AC 116, [1944] UKHL 1 (03 April 1944); Awolowo v Zik Enterprises Ltd [1958] UKPC 19 (2 October 1958); Duffy v News Group Newspapers Ltd (No 2) [1994] 3 IR 63, [1994] 1 ILRM 364 (SC); Financial Conduct Authority v Macris [2015] EWCA Civ 490 (19 May 2015).

In Dyson v Channel Four Television Corporation [2022] EWHC 2718 (KB) (31 October 2022) at first instance, Nicklin J said:

18. It is an essential element of the cause of action for defamation that the words complained of should be published “of and concerning” the claimant: Knuppfer v London Express Newspaper Ltd [1944] AC 116, 121 [1944] UKHL 1 (03 April 1944)

19. It is not necessary for the claimant to be named. There may be some other way in which the hypothetical ordinary reasonable reader would identify him/her: Economou v de Freitas [2017] EMLR 4, [2016] EWHC 1853 (QB) (27 July 2016) [9] …

21. The identifying material may be … established by proof of specific facts that would cause the reader (with knowledge of those facts) to understand the words to refer to the claimant (extrinsic identification or ‘reference innuendo’): Monir v Wood [2018] EWHC 3525 (QB) (19 December 2018) [95]. … An example of … [this] category is supplied by the facts of [Morgan v Odhams Press Ltd [1971] 1 WLR 1239 (HL)]; reference in the article to a “dog-doping gang” which the claimant contended would be understood to refer to him by readers with knowledge of extrinsic facts.

22. If the claimant relies upon extrinsic facts to establish reference, then s/he must plead and prove those facts. If those facts are proved (or admitted), the issue becomes whether a reasonable person knowing some, or all of, these facts reasonably believes that the publication referred to the claimant. …

26. Indeed, at common law, to establish a cause of action for defamation, it is not necessary for the claimant to adduce evidence that actual publishees understood the words of the publication to refer to the claimant. The test of reference/identification is wholly objective: Economou [11]; Lachaux v Independent Print Ltd [2016] QB 402, [2015] EWHC 2242 (QB) (30 July 2015) [15]; and Monir [96]. Evidence relied upon by the claimant to establish that publishees did understand the publication to refer to him/her is admissible, but not determinative, on the issue of reference: Monir [103] …

On appeal, [2023] EWCA Civ 884 (25 July 2023), Dingemans and Warby LJJ (in a joint judgment; Briss LJ concurring) held

33. … The purpose of the law of defamation is to enable a person to obtain a remedy if their reputation has been unjustifiably diminished by a statement published to one or more other people. … A cause of action requires the … [publication complained of] to be “of and concerning” the claimant … If the reasonable reader or viewer would understand the statement in a defamatory meaning and would take it to be about the claimant, an action should lie. …

35. [In general terms a claimant may be proved to be the person identified or referred to in a statement if] … a claimant is identified or referred to by particular facts known to individuals. This has been called in the textbooks “reference innuendo” (and which the judge called “extrinsic reference”). It is common ground that those particular facts need to be pleaded in the Particulars of Claim and the issue of identification or reference decided on the facts found to be proved. …

[Update (04 October 2023)]: An equally wide approach seems to be taken in other private law contexts, including invasion of privacy claims similar to that being taken by Mr Kenny. For example, in Green Corns Ltd v CLA Verley Group Ltd [2005] EWHC 958 (QB) (18 May 2005) [h/t Andrew Scott] Tugendhat J granted an injunction restraining a local newspaper from publishing the addresses of homes provided for troubled children. The Article 8 ECHR privacy rights of the children placed in its care were engaged on the facts, and were protected by means of the equitable action for breach of confidence and the tort of misuse of private information. Tugendhat J held that “the home address of an individual is information the disclosure and use of which that individual has a right to control in accordance with Article 8” ([53]) and that the “fact that no child has been named by the newspaper is immaterial. The mischief … can arise as readily if a child is identified by an address as by a name” [(61)].

Similarly, in Secretary of State for the Home Department v TLU [2018] 4 WLR 101, [2018] EWCA Civ 2217 (15 June 2018) [h/t Inforrm] Gross LJ held that, for the purposes of common law and data protection claims, the wife and child of a person whose data had been inadvertently published were also identifiable, even though they had a different surname, and their relationship could only be derived from extraneous data ([31], [39]). [End update]

There are also some interesting cases on when general references can sufficiently identify a plaintiff to support a claim for breach of the General Data Protection Regulation (Regulation (EU) 2016/679 of 27 April 2016; the GDPR). For example, Article 4(1) GDPR provides

‘personal data’ means any information relating to an identified or identifiable natural person (‘data subject’); an identifiable natural person is one who can be identified, directly or indirectly, in particular by reference to an identifier such as a name, an identification number, location data, an online identifier or to one or more factors specific to the physical, physiological, genetic, mental, economic, cultural or social identity of that natural person;

And Recital 26 GDPR provides in part:

… To determine whether a natural person is identifiable, account should be taken of all the means reasonably likely to be used, such as singling out, either by the controller or by another person to identify the natural person directly or indirectly. …

The CJEU is taking a very expansive approach to these provisions. In Case C-487/21 FF v Österreichische Datenschutzbehörde; CRIF GmbH (intervening) (ECLI:EU:C:2023:369; CJEU, First Chamber; 04 May 2023) it commented:

23. The use of the expression ‘any information’ in the definition of the concept of ‘personal data’ in that provision reflects the aim of the EU legislature to assign a wide scope to that concept, which potentially encompasses all kinds of information, not only objective but also subjective, in the form of opinions and assessments, provided that it ‘relates’ to the data subject …

24. In that regard, … information relates to an identified or identifiable natural person where, by reason of its content, purpose or effect, it is linked to an identifiable person …

Indeed, in Case C-579/21 JM; Apulaistietosuojavaltuutettu and Pankki S (intervening) (ECLI:EU:C:2023:501; CJEU, First Chamber; 22 June 2023) [42]-[45] it repeated and amplified these points.

The points emerging from these lines of authority are similar: if a reasonable person knowing some, or all of, of necessary facts extrinsic to a newspaper article “reasonably believes” that the article refers to the plaintiff, or if the “content, purpose or effect” of the article is to identify a plaintiff, then the plaintiff will be sufficiently identifiable to pursue a claim. If Kenny’s claim proceeds, it will be interesting to see if these or similar principles are applied.

Bonus: (2022) 14(2) Journal of Media Law contains an excellent symposium on Bloomberg v ZXC [2022] AC 1158, [2022] UKSC 5 (16 February 2022):

And note the analyses, in an earlier volume of the same journal, of some of the above commentators, as the case headed to the Supreme Court:

Considering the evolving landscape of privacy and data protection laws, what challenges and considerations might arise in determining the balance between freedom of expression and protection of individuals’ privacy?

Teknik Informatika