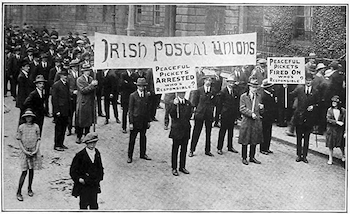

The Postal Strike, 9-29 September 1922 (see here and here) was the first major industrial dispute faced by the new government of the Irish Free State (see Gerard Hanley “They ‘never dared say “boo” while the British were here’: the postal strike of 1922 and the Irish Civil War” (2022) 46 (169) Irish Historical Studies 119). The government imposed various restrictions, including a ban on pickets. Nevertheless, the picture on the left (taken from The Graphic newspaper, 16 September 1922) shows the Postal Unions on the march in Dublin. More than a century later, the government continues to restrict the political activities of civil servants. In my previous post, we saw that the Civil Service Code of Standards and Behaviour (2004; revised 2008 (pdf); Circular 26/04 (09 September 2004) (pdf)) and Civil Servants and Political Activity (Circular 09/2009 (30 April 2009) (pdf)) provide for a blanket ban on civil servants engaging in any form of political activity or speaking in public on matters of local or national political controversy. My previous post considered whether the two circulars provided a sufficient legal basis for the ban. In this post, I want to consider whether the restrictions in the two circulars are constitutional.

The Postal Strike, 9-29 September 1922 (see here and here) was the first major industrial dispute faced by the new government of the Irish Free State (see Gerard Hanley “They ‘never dared say “boo” while the British were here’: the postal strike of 1922 and the Irish Civil War” (2022) 46 (169) Irish Historical Studies 119). The government imposed various restrictions, including a ban on pickets. Nevertheless, the picture on the left (taken from The Graphic newspaper, 16 September 1922) shows the Postal Unions on the march in Dublin. More than a century later, the government continues to restrict the political activities of civil servants. In my previous post, we saw that the Civil Service Code of Standards and Behaviour (2004; revised 2008 (pdf); Circular 26/04 (09 September 2004) (pdf)) and Civil Servants and Political Activity (Circular 09/2009 (30 April 2009) (pdf)) provide for a blanket ban on civil servants engaging in any form of political activity or speaking in public on matters of local or national political controversy. My previous post considered whether the two circulars provided a sufficient legal basis for the ban. In this post, I want to consider whether the restrictions in the two circulars are constitutional.

In Bright v Minister for Defence [2024] IEHC 289 (14 May 2024), the plaintiff considered that the Order precluded him from attending a peaceful assembly and protest being organised by theWives and Partners of the Defence Forces (WPDF), and this was sufficient to provide him with locus standii to bring the proceedings ([138]; compare RID Novaya Gazeta and ZAO Novaya Gazeta v Russia 44561/11, [2021] ECHR 383 (11 May 2021) [59]). Similarly, any civil servant who considers that Circulars 26/04 and 09/2009 preclude them from attending a similar peaceful assembly and protest would have locus standii to challenge those two circulars. A fortiori civil servants who are disciplined pursuant to the circulars. In Bright, Sanfey J held that the Order was a disproportionate restriction on the plaintiff’s constitutional rights. Similarly, it is clear that the validity of individual circulars can be challenged on constitutional grounds (eg, Mulloy v Minister for Education [1975] IR 88 (SCt); Greene v Minister for Agriculture [1990] 2 IR 17 (Murphy J); CA v Minister for Justice and Equality [2014] IEHC 532 (14 November 2014)).

So, the question arises here as to whether the two circulars constitute disproportionate restrictions on civil servants’ constitutional rights. They plainly engage the freedom of political expression, concerned with the public activities of citizens in a democratic society, protected by Article 40.6.1(i) of the Constitution (see Murphy v Irish Radio and Television Commission [1999] 1 IR 12, 24, [1998] 2 ILRM 360, 372, (28 May 1998) [37]-[44] (doc | pdf) (Barrington J; Hamilton CJ, O’Flaherty, Denham, and Keane JJ concurring)). In an earlier post, we saw that, in the US, political speech is central to the meaning and purpose of the First Amendment, triggering strict scrutiny, by which the state must demonstrate that a restriction is narrowly tailored to serve a compelling state interest. Similarly, under Article 10 of the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR), freedom of expression constitutes one of the essential foundations of a democratic society, at the very core of which is freedom of political debate. There is, therefore, little scope under Article 10(2) ECHR “for restrictions on freedom of expression in the fields of political speech and other matters of public interest” (Assotsiatsiya NGO Golos v Russia 41055/12, [2021] ECHR 932 (16 November 2021) [89]). The conclusion to be drawn is that restrictions on political speech must satisfy the strictest of scrutiny or the strongest application of the proportionality test.

Restrictions on expression pursuant to Article 10(2) ECHR must, in the first instance, be “prescribed by law” (a condition not satisfied in Magyar Kétfarkú Kutya Párt v Hungary 201/17, [2020] ECHR 59 (20 January 2020)). In my previous post, we saw that, as a matter of domestic law, circulars do “not have the force of law” (Browne v An Bord Pleanála [1991] 2 IR 209, 220 (Barron J)), and certainly do not have statutory “force” or “effect” (McEneaney v Cavan and Monaghan Education and Training Board [2016] IECA 53 (02 March 2016) [31]-[36] (Ryan P; Peart and Hogan JJ concurring); and see Conor Casey “Under-explored Corners: Inherent Executive Power in the Irish Constitutional Order” (2017) 40(1) Dublin University Law Journal (ns) 1, 33 (SSRN)). That may call into question whether restrictions in Circulars 26/04 and 09/2009 can properly be said to be prescribed by law. On the other hand, that condition “also refers to the quality of the law in question, which should be accessible to the person concerned and foreseeable as to its effects” (RFE/RL Inc v Azerbaijan 56138/18, [2024] ECHR 517 (13 June 2024) [88]), and it is certainly the case that the two circulars are accessible and foreseeable as to their effects.

Restrictions on expression pursuant to Article 40.6.1(i) of the Constitution and Article 10(2) ECHR must pursue a legitimate aim (a condition not satisfied in Suprun v Russia 58029/12, [2024] ECHR 536 (18 June 2024)). It is very likely that the Court would accept that ensuring public “confidence in the political impartiality of the Civil Service” would provide the State with a prima facie justification for the restriction upon constitutional rights contained in the two circulars (see, mutatis mutandis, Rekvényi v Hungary 25390/94, (2000) 30 EHRR 519, [1999] ECHR 31 (20 May 1999) [41], [46])).

Restrictions on expression pursuant to Article 40.6.1(i) and Article 10(2) must be proportionate to that aim. It is far from clear that the blanket ban in the two circulars would be proportionate to the aim of ensuring public confidence in the political impartiality of the Civil Service. In Bright, Sanfey J held that the broad prohibitions in the Order constituted a disproportionate restriction on the right to freedom of assembly protected by Article 40.6.1(iii) of the Constitution. It may very well prove to be the case that, by analogy, the blanket ban in the two circulars would likewise constitute a disproportionate restriction not only Article 40.6.1(iii) but also upon the freedom of political expression protected by Article 40.6.1(i).

Certainly, it is hard to see how prohibitions by which civil servants are “totally debarred from engaging in any form of political activity”, or prohibited from engaging “in public debate … on politics”, from contributing “to public debate”, or from speaking “in public on matters of local or national political controversy”, impair the freedom of political expression “as little as possible”. As with the Order at issue in Bright, the blanket ban in these two circulars seems to go much further than necessary. Indeed, whilst the constitutional necessity to impair the freedom of political expression “as little as possible” would seem to require that the definition of political speech subject to restrictions should be as narrow as possible, the definition of “politics” in Circular 26/04 heads in precisely the opposite direction, seeking to define it as broadly as possible.

On the other hand, in the US, practical realities, such as the need for efficiency and effectiveness in government service, may justify restrictions upon the political speech protected by the First Amendment, provided they are content neutral and appropriately limited. But bans on political speech are not content neutral, and blanket bans are not appropriately limited. Moreover, the European Court of Human Rights has held that civil servants qualify for the protection of Article 10 of the Convention (Vogt v Germany 17851/91, (1996) 21 EHRR 205, [1995] ECHR 29 (26 September 1995) [53]; Eminagaoglu v Turkey 76521/12, [2021] ECHR 180 (09 March 2021) [120]), and it is hard to see how blanket bans on political speech can be said to be necessary and proportionate.

Of course, even quite extensive restrictions on speech may be held to be proportionate, if other means of expression remain available. For example in Murphy v Irish Radio and Television Commission [1999] 1 IR 12, 24, [1998] 2 ILRM 360, 372, (28 May 1998) [37]-[44] (doc | pdf), the Supreme Court upheld the constitutionality of a ban on religious advertising in section 10(3) of the Radio and Television Act, 1988 (the 1988 Act). Barrington J (Hamilton CJ, O’Flaherty, Denham, and Keane JJ concurring) [47] held that the appellant “has the right to advance his views in speech or by writing or by holding assemblies or associating with persons of like mind to himself. He has no lesser right than any other citizen to appear on radio or television. The only restriction placed upon his activities is that he cannot advance his views by a paid advertisement on radio or television”. This reasoning was approved by the European Court of Human Rights in Murphy v Ireland 44179/98 (2003) 38 EHRR 212, [2003] ECHR 352 (10 July 2003) [74]-[75]. This is so even in the context of political speech: similar restrictions on political advertising have been upheld in the High Court (Colgan v Irish Radio and Television Commission [2000] 2 IR 490, [1999] 1 ILRM 22, [1998] IEHC 117 (20 July 1998)) and in the European Court of Human Rights (Animal Defenders International v UK 48876/08 (2013) 57 EHRR 21, [2013] ECHR 362 (22 April 2013)). Indeed, this is so even in the context of political speech of police officers: in Rekvényi v Hungary (above) [49], the Court upheld a prohibition on police offices from joining political parties: it was not “an absolute ban on political activities”; rather the police officers “remained entitled to undertake some activities enabling them to articulate their political opinions and preferences”. On the other hand, Circulars 26/04 and 09/2009 amount to an absolute ban on political activities, and provide no alternative means by which civil servants can express their political opinions.

Moreover, the the European Court of Human Rights requires significant democratic safeguards to uphold such restrictions. In Murphy [73], the Court pointed to the “detailed” Oireachtas debate about section 10(3) of the 1988 Act; and, in Animal Defenders, the Court affirmed that the “quality of the parliamentary and judicial review of the necessity of the measure is of particular importance” ([108], referring, inter alia, to Murphy [73]; see also Orlovskaya Iskra v Russia 42911/08, [2017] ECHR 197 (21 February 2017) [113]; Novikova v Russia 25501/07, [2016] ECHR 388 (26 April 2016) [194]; Bayev v Russia 67667/09, [2017] ECHR 572 (20 June 2017) [63]; Lings v Denmark 15136/20, [2022] ECHR 314 (12 April 2022) [42]). Hence in Orlovskaya Iskra v Russia, in finding that election-related restrictions breached Article 10, the Court was unimpressed that it had at its disposal no information relating to the quality of the parliamentary review of the restriction (42911/08, [2017] ECHR 197 (21 February 2017) [126]; see also OOO Informatsionnoye Agentstvo Tambov-Inform v Russia 43351/12, [2021] ECHR 400 (18 May 2021) [79]). Here, since the two circulars are simply written statements issued by a Minister, then, by their very nature, there has been no debate at all about them in the Oireachtas. This absence of parliamentary review may prove fatal to the ban on civil servants’ speech in a way that would not apply to the statutory ban in section 103(1A) of the Defence Act, 1954 Act as inserted by section 11 of the Defence (Amendment) Act 2024 (here and here (pdfs)), which had significant (if not necessarily satisfactory) legislative review.

In Murphy, Barrington J distinguished the restriction in section 10(3) of the 1998 Act from Cox v Ireland [1992] 2 IR 503: there, he said, “a person who had violated the relevant section in even a minor way was liable to lose his job (if he was a public servant) and to be barred forever from obtaining employment in the public service”. On this view, whereas, in Murphy, the ban was “minimalist” ([47]) and proportionate, the blanket ban in Cox was “impermissibly wide and indiscriminate” (524 (Finlay CJ)) and thus disproportionate. Likewise, in Holland v Governor of Portlaoise Prison [2004] 2 IR 573, [2004] IEHC 97 (11 June 2004) McKechnie J held that a blanket ban on prison visits by journalists was “entirely disproportionate”. Again, in NvH v Minister for Justice & Equality [2018] 1 IR 246, [2017] 1 ILRM 105, [2017] IESC 35 (30 May 2017) held that a blanket ban on seeking employment was unconstitutional. Similarly, in Egan v Governor of Cloverhill Prison [2024] IECA 111 (07 May 2024), the Court of Appeal held that imposing a blanket prohibition on visiting any prisoner for an indefinite period does not respect the principles of proportionality. In Bright, Sanfey J held that the Order was a disproportionate restriction on the plaintiff’s constitutional rights that went much further than necessary. It is hard to see how a similar conclusion could be avoided by the blanket bans imposed here by Circulars 26/04 and 09/2009.

Thanks Eoin, excellent series, very interesting and closely argued.

Thanks, Ray. You’re very kind.