Growing up, I remember a tv programme about technology repeating the aphorism that

Growing up, I remember a tv programme about technology repeating the aphorism that

To err is human; to really foul things up requires a computer

Like many pithy axions, its first usage is unclear. And I don’t remember the particular tv programme on which I heard it. But it is well illustrated today by the following story:

Airline mistakenly sells hundreds of first-class tickets at heavily reduced prices

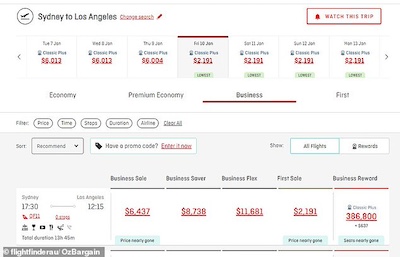

Qantas … had flights between Australia and the US displayed on its website on Thursday, but instead of advertising the usual rate for these journeys, an error made the flights appear to be up to 85 per cent less than the usual first-class prices. …

The relevant error is pictured above, left. Though it does not appear on the Quantas news site, a statement by a Qantas spokesperson cited a coding error, and said this was “a case where the fare was actually too good to be true”. If something looks too good to be true, that’s because it usually is. And this is not the first time that an airline’s website has really fouled things up. For example, in 2008, an Irish airline listed transatlantic business-class flights for €5 plus taxes; in 2012, a US airline listed flights to Hong Kong at four air-miles plus taxes and fees, or about $35; and, in 2018, a UK airline listed flights between Dubai and Tel Aviv for £1.

I have blogged several times about what happens when a retailer makes a mistake on a website and offers goods or services at a significant, unintended, discount. When someone seeks to accept such offers, various questions arise: (1) has that offer been accepted, so that there is a contract?; (2) if so, is it affected by the mistake?; (3) if not, (a) do its terms permit it to be cancelled; and (b) if so, are such terms fair?; (4) have any additional protections and cooling-off periods been complied with; and (5) if there are any claims, what are the available remedies?

For example, on the issue of mistake, in People (DPP) v Dillon [2002] 4 IR 501 (CCA), Hardiman J (Finnegan P and Ó Caoimh J concurring) held that, in cases of induced unilateral mistake, there is no consensus between the parties, and the contract is void. And, in Leopardstown v Templeville [No 2] [2013] IEHC 526 (02 September 2013) Charleton J said that “unilateral mistake, may occur where one of the parties is mistaken as to some element of the agreement. This does not automatically render an agreement void: more is needed, such as an exploitation of that mistake by the other party. … When one party to a contract realises that the other party is making a mistake and engages in sharp practice with a view to ensuring the benefit of that error to itself, the contract will be rendered void from its inception” (see also McMahon v O’Loughlin [2005] IEHC 196 (9 June 2005) [13.6] (Murphy J); Charleton J was reversed on appeal on a different issue ([2015] IECA 164 (28 July 2015)) and the Court of Appeal was further reversed by the Supreme Court and the judgment of Charleton J on that issue was restored ([2017] IESC 50 (11 July 2017)). Australian law is to the same effect (see Taylor v Johnson (1983) 151 CLR 422, [1983] HCA 5 (23 February 1983)). So, when a retailer makes a mistake on a website and offers goods or services at significant, unintended, discount, it will almost always be clear that the customer will have realised that the retailer is making a mistake and will have engaged in sharp practice with a view to ensuring the benefit of that error to itself, so the contract will be void, and neither party can rely on it (see also Samuel Becher & Tal Zarsky “Big Mistake(s)” Florida Law Review (forthcoming 2024) (SSRN). The best that a customer can hope for here is to recover the purchase price paid. On the other hand, if the contract is not void for mistake, then the mistaken retailers’ terms and conditions will usually be enough to protect them. So it proved here. Section 3.12 of the Quantas Conditions of Carriage provides:

Errors and mistakes

Sometimes mistakes are made and incorrect fares can be displayed. If there is an error or mistake that is reasonably obvious in the fare price and you have a Ticket and/or a confirmed booking, we may:

(a) cancel the Ticket and/or booking;

(b) provide you with a refund …;

(c) offer you a new Ticket at the correct fare price as at the time of the booking; and

(d) in the event that you accept the offer and pay the correct fare issue you with a new Ticket.

On foot of this, the Quantas spokesperson said that, as “a gesture of good will, we’re rebooking customers in business class at no additional cost … Customers also have the option of a full refund”. Nevertheless, the cases are not always straightforward; and, in addition to the airline cases above, I have considered them where

- in Ireland, an upmarket retail store’s website listed designer trainers at €10;

- in the UK, a supermarket website listed premium whisky for £2.50;

- in the UK, another supermarket website listed large bottles of Budweiser for just 14p;

- an online retailer listed a 3D plasma tv for €6.49 plus VAT;

- in Ireland, a publisher listed a €395 book for €136;

- in Ireland, a department store website listed a €1,400 tv for €98;

- in the US, a discount retailer listed a big-screen tv for $9.99 (other examples are given in that post); and

- in Chile, a computer retailer’s website subtracted money for upgrades rather than adding it.

This mistake by Qantas simply adds to the list. Doubtless they are grateful for section 3.12 of their Conditions of Carriage. And, assuredly, lawyers for other online retailers are checking theirs. If and when the retailers’ computers foul things up again, only well drafted terms and conditions will save them! So, the moral of the story is: if to err is human, and if to really foul things up requires a computer, then it takes a lawyer to save the day!!