In a previous post, I examined the judgment of Roy J in the the Federal Court of Canada in 1395804 Ontario Ltd (Blacklock’s Reporter) v Canada (Attorney General) 2024 FC 829 (CanLII) (31 May 2024) [Blacklock’s Reporter], effectively holding that technological protection measures cannot defeat users seeking to rely on the exceptions provided in the copyright legislation. And I put it in the context of sections 370, 374 and 376 of the Copyright and Related Rights Act, 2000 (hereafter: CRRA), and of section 377 CRRA (as inserted by section 38 of the Copyright and Other Intellectual Property Law Provisions Act 2019.

In a previous post, I examined the judgment of Roy J in the the Federal Court of Canada in 1395804 Ontario Ltd (Blacklock’s Reporter) v Canada (Attorney General) 2024 FC 829 (CanLII) (31 May 2024) [Blacklock’s Reporter], effectively holding that technological protection measures cannot defeat users seeking to rely on the exceptions provided in the copyright legislation. And I put it in the context of sections 370, 374 and 376 of the Copyright and Related Rights Act, 2000 (hereafter: CRRA), and of section 377 CRRA (as inserted by section 38 of the Copyright and Other Intellectual Property Law Provisions Act 2019.

There have been subsequent relevant developments, in Canada and the US, and I want to look at those developments in this post. In particular, the US development – inevitably – adds the First Amendment to the mix, which in turn raises questions about whether there are similar constitutional issues in Canada and Ireland.

First, Canada. Barry Sookman argues that the case is riddled with mistakes, that many of its findings are open to significant doubt, and that it cries out for appellate review. In reply, Howard Knoff, argues that Sookman’s arguments are against a straw man. As my analysis in my previous post makes clear, I think that Knoff has the better of this argument.

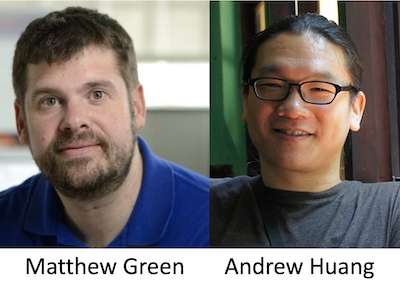

Second, the US. Matthew Green (a computer science professor investigating the security of electronic systems) and Andrew (‘Bunnie‘) Huang (a tech inventor of a device to format-shift protected content) challenged the anti-circumvention provisions in the Digital Millennium Copyright Act (17 USC §1201 et seq), which forbid, inter alia circumventing technological measures that control access to copyright works (17 USC §1201(a)(1)(A)) or descrambling or decrypting protected works (17 USC §1201(a)(3)(A)) (the anti-circumvention provisions). These provisions are subject to statutory and regulatory exemptions. In particular, the DMCA also provide for a triennial procedure by which the Librarian of Congress can provide for exemptions from the anti-circumvention provisions to people who are or are likely to be adversely affected by the anticircumvention provision in their ability to make non-infringing uses of copyrighted materials (17 USC §1201(a)(1)(C)) (the triennial rule-making process). In the 2015 rule-making cycle, the Librarian of Congress, after application by Green, provided for an exemption that was too narrow for his purposes. A further DMCA provision, not subject to the triennial exemption procedure, prohibits trafficking in any anti-circumvention technology (17 USC §1201(a)(2)(A)-(C) (the anti-trafficking provision), which has been used to prevent hackers from circulating a software that breaks the encryption controlling unauthorized access to or copying of DVDs (Universal City Studios Inc v Corley 273 F3d 429 (2d Cir, 2001)). Green and Huang, represented by the Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF), challenged the constitutionality of these provisions.

In the US, the courts distinguish between facial challenges and as-applied challenges, especially in the First Amendment context. A successful facial challenge finds the restriction unconstitutional in every application, and it is no more. A successful as-applied challenge finds the restriction unconstitutional only as applied to the individual, leaving it otherwise intact. The Court prefers to consider as-applied challenges, except in the First Amendment context, where facial challenges will be successful where substantial number of the restriction’s applications are unconstitutional, judged in relation to the statute’s plainly legitimate sweep (Moody v NetChoice LLC and NetChoice LLC v Paxton 603 US __ (2024)). Furthermore, even where a facial challenge has been rejected, the restriction might nevertheless be susceptible to an as-applied challenge. Moreover, in the First Amendment context, the overbreadth doctine may be a specific example of a facial challenge. A restriction will be unconstitutionally overbroad where it sweeps too broadly and penalizes a substantial amount of constitutionally protected speech (Reno v ACLU 521 US 844 (1997)). Green and Huang challenged the constitutionality of the anti-circumvention and anti-trafficking provisions, on the grounds that they unduly stifled the fair use of copyrighted works, and thus that they were facially over-broad, and that, as applied, they unconstitutionally burdened the plaintiffs’ specific expressive activities. They also challenged the triennial rule-making process as a speech-licensing regime amounting to a prior-restraint.

On a motion by the defendants to dismiss the plaintiffs’ claims, in Green v Department of Justice 392 FSupp 3d 68 (DDC, 2019) Sullivan J in the US District Court for the District of Columbia rejected most of the plaintiffs’ First Amendment claims. He did accept that the DMCA burdened the use and dissemination of computer code, thereby implicating the First Amendment (see Universal v Corley (above)). On the plaintiffs’ facial challenges, he rejected their standing to argue that the DMCA inhibits fair use rights and is unconstitutionally overboard; and he held that they had not sufficiently alleged facts to state a claim that the exemption rule-making process is an unconstitutional speech-licensing prior restraint. On their as-applied challenges to the anti-circumvention provisions, Sullivan J held that they were content-neutral restrictions on speech, thereby triggering intermediate, rather than strict, scrutiny, by which a provision will be upheld if (i) it furthers a substantial governmental interest; (ii) the interest furthered is unrelated to the suppression of free expression; and (iii) the provisions do not burden substantially more speech than is necessary to further the government’s interest (Turner Broadcasting Systems Inc v Federal Communications Commission 512 US 622, 662 (1994) (Kennedy J)). The plaintiffs conceded that (i) the government had a substantial interest in addressing massive copyright piracy, and (ii) that that interest is unrelated to the suppression of free expression. And Sullivan J concluded that the plaintiffs had alleged facts sufficient to state a claim that section 1201, as applied to their intended conduct, violates the First Amendment, and accordingly denied the defendants’ motion to dismiss the plaintiffs’ claim in this respect. However, in the later Green v Department of Justice (No 16-1492) Sullivan J (DCC, 15 July 2021) and the Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit (54 F4th 738 (DC Cir, 2022)) dismissed the plaintiffs’ as-applied claims, on the grounds that the Librarian of Congress had, in the 2018 rule-making cycle, granted a sufficient exemption for Green’s security research, and that the anti-trafficking provisions would not preclude the publication by him of an academic book containing detailed information regarding how to circumvent security systems, but that Huang’s proposed device would likely lead to widespread piracy.

On a motion by the defendants to dismiss the plaintiffs’ claims, in Green v Department of Justice 392 FSupp 3d 68 (DDC, 2019) Sullivan J in the US District Court for the District of Columbia rejected most of the plaintiffs’ First Amendment claims. He did accept that the DMCA burdened the use and dissemination of computer code, thereby implicating the First Amendment (see Universal v Corley (above)). On the plaintiffs’ facial challenges, he rejected their standing to argue that the DMCA inhibits fair use rights and is unconstitutionally overboard; and he held that they had not sufficiently alleged facts to state a claim that the exemption rule-making process is an unconstitutional speech-licensing prior restraint. On their as-applied challenges to the anti-circumvention provisions, Sullivan J held that they were content-neutral restrictions on speech, thereby triggering intermediate, rather than strict, scrutiny, by which a provision will be upheld if (i) it furthers a substantial governmental interest; (ii) the interest furthered is unrelated to the suppression of free expression; and (iii) the provisions do not burden substantially more speech than is necessary to further the government’s interest (Turner Broadcasting Systems Inc v Federal Communications Commission 512 US 622, 662 (1994) (Kennedy J)). The plaintiffs conceded that (i) the government had a substantial interest in addressing massive copyright piracy, and (ii) that that interest is unrelated to the suppression of free expression. And Sullivan J concluded that the plaintiffs had alleged facts sufficient to state a claim that section 1201, as applied to their intended conduct, violates the First Amendment, and accordingly denied the defendants’ motion to dismiss the plaintiffs’ claim in this respect. However, in the later Green v Department of Justice (No 16-1492) Sullivan J (DCC, 15 July 2021) and the Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit (54 F4th 738 (DC Cir, 2022)) dismissed the plaintiffs’ as-applied claims, on the grounds that the Librarian of Congress had, in the 2018 rule-making cycle, granted a sufficient exemption for Green’s security research, and that the anti-trafficking provisions would not preclude the publication by him of an academic book containing detailed information regarding how to circumvent security systems, but that Huang’s proposed device would likely lead to widespread piracy.

On remand, the plaintiffs discontinued their as-applied claims. Once the District Court entered final judgment, the plaintiffs appealed that court’s earlier order dismissing their facial First Amendment challenges to the Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit. In Green v Department of Justice (No 23-5159; DC Cir, 2 August 2024), the DC Court of Appeals (Pillard J; Henderson and Millett JJ concurring) dismissed their facial challenges.

Unlike Sullivan J, Pillard J began by discussing fair use. The First Amendment guarantees freedom of speech, whilst the Copyright Clause secures “for limited Times to Authors … the exclusive right to their respective writings …” (Article I(8)(8)), but these are not in tension because the Copyright Clause bolsters the First Amendment by acting as an “engine of free expression” (Harper & Row Publishers Inc v Nation Enterprises 471 US 539, 558 (1985) (O’Connor J); Golan v Holder 565 US 302 327-28 (2012) (Ginsburg J)). However, the fair use doctrine, an affirmative defence provided by 17 USC §107, permits the use of copyrighted work “for purposes such as criticism, comment, news reporting, teaching, … scholarship, or research …”; it is a traditional First Amendment safeguard designed to strike a balance between expression and prohibition in copyright law (Eldred v Ashcroft 537 US 186, 220 (2003) (Ginsburg J)). However, section 1201(c) provides that nothing in the section “shall affect rights, remedies, limitations, or defenses to copyright infringement, including fair use, … (17 USC § 1201(c)(1); emphasis added)) (in Universal v Corley (above), the Court held that the facts did not amount to fair use). The express reference to defences here makes the DMCA more like the Irish position (see section 374 CRRA) than the Canadian, but it would have been interesting to see if a process of reasoning similar to that of Roy J in Blacklock’s Reporter would have reached a similar result in the context of the DMCA.

But the plaintiffs’ argument went further. They argued that all fair use is protected by the First Amendment, so section 1201(a) could not validly prohibit circumvention by individuals for the purpose of making fair use of copyrighted works in the first place. Pillard J concluded that this assumption erroneously overstated the role of the First Amendment in the context of fair use (which is set out above). He went on to observe that facial invalidation of a statute for overbreadth is strong medicine that is not to be casually deployed; accordingly, facial overbreadth challenges are by design “hard to win” (Moody v NetChoice (above) slip op at 9 (Kagan J)). The plaintiffs argued that there were numerous specific categories of third-party speech impermissibly burdened by Section 1201(a), which together overshadowed legitimate applications of the law. Pillard J disagreed: the First Amendment, he said, “does not guarantee potential fair users unfettered or privileged access to copyrighted works they seek to use in their own expression. To hold otherwise would defy the First Amendment’s solicitude of speakers’ control over their own speech” (referring to Harper & Row v Nation Enterprises 471 US 539, 559 (1985) (O’Connor J)).

On the First Amendment challenge undiluted by fair use concerns, the plaintiffs largely conceded that the constitutionality of section 1201(a) as applied to them was controlled by intermediate scrutiny. And Pillard J had no trouble concluding, like Sullivan J, that the anti-circumventions provisions satisfied that test:

… section 1201(a) furthers a substantial governmental interest in fostering the widespread availability of copyrighted digital work on a content-neutral basis, and that interest would be sharply curtailed in the absence of enforceable technological protections … plaintiffs have made no plausible allegations that section 1201(a)’s protection against circumvention of digital locks somehow unnecessarily burdens … speech. Indeed, any constitutionally cognizable burden is slight …

Section 1201(a) is constitutionally applied as to a wide range of non-expressive conduct that involves circumvention and trafficking, and its application to copyrighted expression readily withstands First Amendment scrutiny. … Plaintiffs’ highly particularized yet underdeveloped examples simply do not add up to the “lopsided ratio” of unconstitutional applications required to sustain a facial challenge.

As to the authority of the Librarian of Congress to grant exemptions to the anti-circumvention provision, Pillard J observed that “what the fair use defense does for copyright infringement, the exemptions do for section 1201(a)”: the exemptions and a “dynamic” regulatory exemption scheme “blunt the anti-circumvention provision’s incidental burdens on non-infringing — ie, fair — uses”. He repeated the constitutional bromide that a prior restraint bears a heavy presumption against its constitutional validity (the leading case is New York Times Co v United States 403 US 713 (1971) (the Pentagon Papers case)). But he concluded that the DMCA’s authorization of regulatory exemptions did not operate as a prior restraint on speech; rather it was a generally applicable laws not aimed at expression or conduct commonly associated with expression.

Effectively, then, the range of the fair use doctrine, and the functionally equivalent triennial exemption procedure, together sufficiently protected the First Amendment interests at issue here, at least insofar as the anti-circumvention provisions are concerned. But the anti-trafficking provisions, which are not subject to the triennial exemption procedure, only get to rely on the fair use doctrine. However, this is likely a distinction without a difference, and is unlikely to be a sufficient gap to justify an appeal to the Supreme Court. That Court has grappled with fair use each term for the last three years (see Google LLC v Oracle America Inc 593 US __ (2021); Andy Warhol Foundation for Visual Arts Inc v Goldsmith 598 US __ (2023); Jack Daniel’s Properties Inc v VIP Products LLC 599 US __ (2023)) and may very well feel that it has said all that it has got to say on the topic for now. There is far more to be said about the inter-relationship between the First Amendment and the fair use doctrine than the bland platitudes from Harper & Row, Golan v Holder, and Eldred v Ashcroft quoted by Pillard J in Green v DOJ. However, a First Amendment-infused fair use argument did not really find much favour in Jack Daniel’s, so I think it unlikely that this issue will return to the Supreme Court for the time being.

However, the structure of Green v DOJ, asking whether the balance of anti-circumvention provisions and applicable exceptions like fair use is consistent with constitutional speech concerns, also arises in Canada and Ireland. In Canada, in Blacklock’s Reporter, there was no reference to the freedom of expression protected by section 2(b) of the Charter, but it would surely have bolstered Roy J’s conclusions, and may very well do so on any appeal. And, for reasons similar to those given by Sullivan J at first instance and by Pillard J on appeal in Green v DOJ, it is likely that the balance – achieved by interpretation in Blacklock’s Reporter in Canada, and by the application of section 374 CRRA in Ireland – between anti-circumvention and fair dealing would constitute proportionate restrictions upon speech and thus survive constitutional scrutiny both in Canada and in Ireland.

One Reply to “Copyright balance, technological protection measures, and fair use”