Abraham “Bram” Stoker (1847–1912) was an Irish author, best known for writing the 1897 Gothic horror novel Dracula. Stoker drew extensively from Transylvanian folklore and history for the novel, and he gave the title character the name Dracula because he thought it meant “devil” in Romanian.

Abraham “Bram” Stoker (1847–1912) was an Irish author, best known for writing the 1897 Gothic horror novel Dracula. Stoker drew extensively from Transylvanian folklore and history for the novel, and he gave the title character the name Dracula because he thought it meant “devil” in Romanian.

The novel was published in the United Kingdom in 1897 by Archibald Constable and Company, and in the United States in 1899 by Doubleday & McClure. To secure copyright, US law at the time required the author to deposit two copies of a book with the Copyright Office in the Library of Congress. However, in 1930, when Universal Studios purchased the movie rights, it was discovered that Stoker and Doubleday had deposited only one copy, which effectively meant that the book was in the public domain in the US. The novel and its title character have become mainstays of popular culture, and Stoker’s great grand-nephew Dacre Stoker has suggested that Stoker’s failure to comply with US copyright law contributed to the novel’s enduring status, since US writers and producers did not need to pay a licence fee to use the character. That may have been so in the US, but the opposite was the case in Europe.

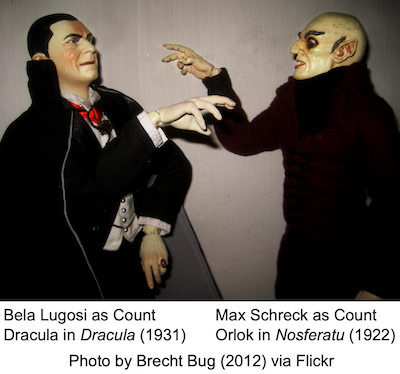

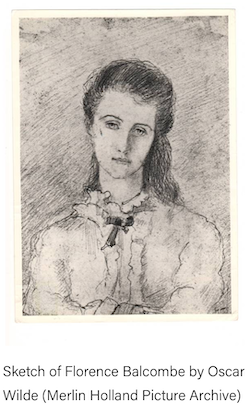

In 1878, Stoker married Dublin society beauty Florence Balcombe (1858-1937) (pictured left), and they moved to London. After he died in 1912, she was his literary executor, and Dracula was her primary source of income, though not a lucrative one. In 1922, she received an anonymous letter from Berlin, bringing to her attention the existence of FW Murnau‘s great movie Nosferatu. Symphony of Horrors (Prana Film, 1922). A handbill at the premiere on 5 March 1922 described the movie as “freely adapted from Bram Stoker’s Dracula“; the shooting script described movie as based on the novel; and the original German intertitles acknowledged Dracula as the movie’s source. Whatever may have subsequently emerged about the fragility of Dracula‘s copyright in the US, there were no such problems in Europe: Stoker had properly registered his London copyright in 1897. So, Florence sued. Prana sought to evade the lawsuit by declaring bankruptcy (making Nosferatu its first and last movie). In 1924, Florence won at first instance; and Parna’s successor appealed, twice. Finally, in July 1925, notwithstanding many deviations from the novel which provided the skeleton of the movie but few of its details, Nosferatu was found to have infringed copyright in Dracula, and the court ordered that the negatives and all prints of the film should be handed over to Florence to be destroyed. The German courts sent agents to seek out copies and negatives of the movie; and Florence informed those who sought to screen it of her new legal right to forbid such screenings. Nevertheless, at least one print of Nosferatu survived. And it found its way to the United States; from that print, every modern copy of the movie has been made. Moreover, as Jonathan Bailey notes, “it’s amazing how many elements of modern vampire lore came not from an attempt to write a better vampire tale, but rather were a failed attempt at avoiding a copyright infringement lawsuit”.

In 1878, Stoker married Dublin society beauty Florence Balcombe (1858-1937) (pictured left), and they moved to London. After he died in 1912, she was his literary executor, and Dracula was her primary source of income, though not a lucrative one. In 1922, she received an anonymous letter from Berlin, bringing to her attention the existence of FW Murnau‘s great movie Nosferatu. Symphony of Horrors (Prana Film, 1922). A handbill at the premiere on 5 March 1922 described the movie as “freely adapted from Bram Stoker’s Dracula“; the shooting script described movie as based on the novel; and the original German intertitles acknowledged Dracula as the movie’s source. Whatever may have subsequently emerged about the fragility of Dracula‘s copyright in the US, there were no such problems in Europe: Stoker had properly registered his London copyright in 1897. So, Florence sued. Prana sought to evade the lawsuit by declaring bankruptcy (making Nosferatu its first and last movie). In 1924, Florence won at first instance; and Parna’s successor appealed, twice. Finally, in July 1925, notwithstanding many deviations from the novel which provided the skeleton of the movie but few of its details, Nosferatu was found to have infringed copyright in Dracula, and the court ordered that the negatives and all prints of the film should be handed over to Florence to be destroyed. The German courts sent agents to seek out copies and negatives of the movie; and Florence informed those who sought to screen it of her new legal right to forbid such screenings. Nevertheless, at least one print of Nosferatu survived. And it found its way to the United States; from that print, every modern copy of the movie has been made. Moreover, as Jonathan Bailey notes, “it’s amazing how many elements of modern vampire lore came not from an attempt to write a better vampire tale, but rather were a failed attempt at avoiding a copyright infringement lawsuit”.

Meanwhile, Florence licenced the playwright Hamilton Deane (another Irishman in London) to produce a play based on the novel in London in 1924; it transferred to Broadway in 1927; and it was the basis of Universal Studios’ iconic 1931 movie Dracula, with Bela Lugosi in the title role. Universal paid Florence US$40,000 – roughly US$584,000 [€538,000] today – allowing her to live out her remaining days in comfort. Dacre Stoker suggests that the story of Nosferatu and Dracula has a relatively happy ending:

Nosferatu remains and Florence got her money for stage and film rights. But most importantly, she set an important, symbolic precedent. Every author, artist and musician should thank [her] for the precedent she helped set.

On the other hand, David Crow on Den of Geek called Florence’s crusade against Nosferatu “the greatest act of attempted vandalism in cinematic history”, and Neil Wilkof writing on IPKat, said

the real horror story here is how the copyright system and, in particular, protection regarding the unauthorized production of a derivative work, nearly put a stake in the heart of an exceptional artistic creation.

Like all good movies, there is one final twist in this tale. In October 1928, when Florence read an article claiming, inaccurately, that Universal Studios had bought the movie rights to Dracula, she took the fight to Hollywood, and compelled Universal to pay for them! It was when they had done so that it was discovered that the novel was effectively in the public domain, as two copies had not been deposited with the Copyright Office. Or so it was thought. However, in 2013, Margaret M Wood, then a legal reference librarian at the Law Library of Congress, established that two copies of the Doubleday & McClure 1899 novel had indeed been deposited with the Copyright Office. Imagine what further havoc Florence might have wreaked in the US had she known!

One Reply to “The horrors of copyright from Dracula to Nosferatu”