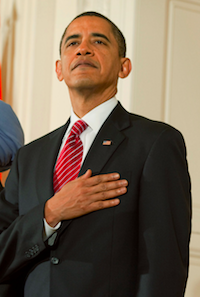

For various reasons (set out here, here, here, and here), I have been musing recently about what should and should not be in a National Anthem Bill. In the US, legislation provides that, when the national anthem (since 1931, “The Star-Spangled Banner“) is being played, “persons present should … stand at attention with their right hand over the heart” (emphasis added). Although the photograph left shows Barak Obama doing so as President in 2009, there was a minor controversy during the 2008 election when he neglected to do so at a campaign event. More recently, US gymnastics gold medalist Gabby Douglas apologized in the face of criticism when she neglected to do so during the playing of national anthem at an olympics medal ceremony. Neither Obama nor Douglas meant anything by it. Obama said his grandfather taught him to put his hand on his heart only during the pledge of allegiance, and only to sing during the national anthem. And Douglas was just overcome by the emotion of the moment.

For various reasons (set out here, here, here, and here), I have been musing recently about what should and should not be in a National Anthem Bill. In the US, legislation provides that, when the national anthem (since 1931, “The Star-Spangled Banner“) is being played, “persons present should … stand at attention with their right hand over the heart” (emphasis added). Although the photograph left shows Barak Obama doing so as President in 2009, there was a minor controversy during the 2008 election when he neglected to do so at a campaign event. More recently, US gymnastics gold medalist Gabby Douglas apologized in the face of criticism when she neglected to do so during the playing of national anthem at an olympics medal ceremony. Neither Obama nor Douglas meant anything by it. Obama said his grandfather taught him to put his hand on his heart only during the pledge of allegiance, and only to sing during the national anthem. And Douglas was just overcome by the emotion of the moment.

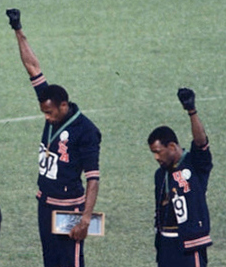

But some people do take advantage of the anthem to make a political point. At the 1968 Olympics, US 200-metre medallists Tommie Smith (gold) and John Carlos (bronze) raised their own gloved hands during the national anthem while looking down as a way of opposing US state-sanctioned racism. In 1996, basketballer Mahmoud Abdul-Rauf of the Denver Nuggets was suspended indefinitely and without pay for declining to stand for the anthem in protest at the treatment of Muslims in the US (though a compromise was soon reached). Jeremy Corbyn, Leader of the opposition Labour Party in the UK, and life-long Republican, caused controversy by not singing the national anthem at a commemorative service for WWII veterans, and caused even more controversy when he sang the anthem at a service to mark the Queen’s 90th birthday with one hand in his pocket.

Most recently, American footballer Colin Kaepernick (quarterback for the San Francisco 49ers) refrains from standing to attention with his hand on his heart during the anthem before football games – he began by remaining seated, but now kneels on one knee. It is his way of opposing racism in the US, and in particular protesting at police brutality against people of colour. He is now being joined in his protest by other athletes in many sports. And just last Sunday, 100 people knelt outside the outside the Bank of America Stadium in Charlotte, North Carolina, as the national anthem played before the Carolina Panthers lost at home to the Minnesota Vikings.

In 1968, Smith and Carlos faced significant criticism for their protest (pictured right). Little has changed. So do Kaepernick and his fellow refuseniks now – indeed, their protests are proving very unpopular with fans. But President Obama, who has invited Smith and Carlos to the White House, has defended Kaepernick and those following his lead, saying that they have the right to protest in this way. As Jeffrey Toobin points out in the New Yorker, this right was copper-fastened in “the most eloquent opinion in the history of the [US] Supreme Court”. The opinion is that of Jackson J in West Virginia State Board of Education v Barnette 319 US 624 (1943), and Toobin says that it “stands as perhaps the greatest defense of freedom of expression ever formulated by a [US] Supreme Court Justice”. Allowing for a little hyperbole, Barnette is certainly a major free speech case, and it equally certainly protects Kaepernick’s protest.

In 1968, Smith and Carlos faced significant criticism for their protest (pictured right). Little has changed. So do Kaepernick and his fellow refuseniks now – indeed, their protests are proving very unpopular with fans. But President Obama, who has invited Smith and Carlos to the White House, has defended Kaepernick and those following his lead, saying that they have the right to protest in this way. As Jeffrey Toobin points out in the New Yorker, this right was copper-fastened in “the most eloquent opinion in the history of the [US] Supreme Court”. The opinion is that of Jackson J in West Virginia State Board of Education v Barnette 319 US 624 (1943), and Toobin says that it “stands as perhaps the greatest defense of freedom of expression ever formulated by a [US] Supreme Court Justice”. Allowing for a little hyperbole, Barnette is certainly a major free speech case, and it equally certainly protects Kaepernick’s protest.

Walter Barnett (his name was misspelled by a court clerk), a Jehovah’s Witness, declined to allow his two daughters to recite the pledge of allegiance in a state grade school; the girls were expelled; but the Supreme Court held that the action of a State in making it compulsory for children in the public schools to salute the flag and pledge allegiance violated the free speech protections in the US constitution. Jackson J, for the majority, wrote (emphasis added):

… the refusal of these persons to participate in the ceremony does not interfere with or deny rights of others to do so. Nor is there any question in this case that their behavior is peaceable and orderly. The sole conflict is between authority and rights of the individual. … To sustain the compulsory flag salute, we are required to say that a Bill of Rights which guards the individual’s right to speak his own mind left it open to public authorities to compel him to utter what is not in his mind. … The very purpose of a Bill of Rights was to withdraw certain subjects from the vicissitudes of political controversy, to place them beyond the reach of majorities and officials, and to establish them as legal principles to be applied by the courts. One’s right to life, liberty, and property, to free speech, a free press, freedom of worship and assembly, and other fundamental rights may not be submitted to vote; they depend on the outcome of no elections.

… freedoms of speech and of press, of assembly, and of worship … are susceptible of restriction only to prevent grave and immediate danger to interests which the State may lawfully protect. … freedom to differ is not limited to things that do not matter much. That would be a mere shadow of freedom. The test of its substance is the right to differ as to things that touch the heart of the existing order. If there is any fixed star in our constitutional constellation, it is that no official, high or petty, can prescribe what shall be orthodox in politics, nationalism, religion, or other matters of opinion, or force citizens to confess by word or act their faith therein.

For similar reasons, the Court has held that burning the US flag is protected symbolic political speech (see Texas v Johnson 491 US 397 (1989); United States v Eichman 496 US 310 (1990); and compare Percy v DPP [2001] EWHC Admin 1125 (21 December 2001)).

In 1996, in respect of Zambia, the UN Human Rights Committee observed that requirements to sing the national anthem as a condition of attending a State school, despite conscientious objection, appears to be an unreasonable requirement and to be incompatible with the right to freedom of thought, conscience and religion guaranteed by the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. Sadly, in a similar case in Japan, the Supreme Court upheld the conviction of a former teacher for handing out leaflets at a high school graduation ceremony objecting to forced worship of the national flag and urging those present to remain seated during the national anthem. Many European States have laws protecting anthems, flags and so on, but the Council of Europe has expressed serious concern as to whether they are compatible with Article 10 of the European Convention on Human Rights. Certainly, the display of totalitarian symbols (Vajnai v Hungary 33629/06 (8 July 2008); Fratanoló v Hungary 29459/10 (3 November 2011)) and controversial flags (Fáber v Hungary 40721/08 (24 July 2012)), is protected under Article 10.

For the purposes of musing on what should and should not be in a National Anthem Bill, the lesson here is to ensure that such political speech is not penalised, and that any formal observance of the anthem should (as in the case of the US legislation cited above) be cast in suggestive, precatory or exhortatory (eg “should” stand at attention) terms rather than in obligatory, prescriptive or binding (eg “shall” stand) language. But we should go no further. It is too easy to go from etiquette to compulsion. As Jackson J warned in Barnette:

Struggles to coerce uniformity of sentiment in support of some end thought essential to their time and country have been waged by many good, as well as by evil, men. … Those who begin coercive elimination of dissent soon find themselves exterminating dissenters. Compulsory unification of opinion achieves only the unanimity of the graveyard.

It seems trite but necessary to say that the First Amendment to our Constitution was designed to avoid these ends by avoiding these beginnings. There is no mysticism in the American concept of the State or of the nature or origin of its authority. We set up government by consent of the governed, and the Bill of Rights denies those in power any legal opportunity to coerce that consent.

In India, section 3 of the Prevention of Insults to the National Honour Act, 1971 (pdf) provides that “whoever intentionally prevents the singing of the Indian National Anthem or causes disturbances to any assembly engaged in such singing” commits an offence. Preventing disturbance is one thing, but penalising non-conformity is quite another. There is still frequent controversy in India when people remain seated for the national anthem before a movie. Indeed, it took a court case in 2005 to decide that merely sitting down does not prevent or disturb the singing of the anthem within the meaning of section 3.

For the purposes of musing on what should and should not be in a National Anthem Bill, the lesson here is to ensure that any provision preventing disturbance of the singing of the anthem cannot be used to punish political dissent or social non-conformity. In an Irish context, the Criminal Justice (Public Order) Acts, 1994 (also here) to 2011 (also here) provide for public order offences, and questions of disturbance of the singing of the anthem should be left to that context. It may be that disorder during the performance of the anthem could be made an aggravating factor in sentencing for a public order offence, but anything more than that, making disturbance of the singing of the anthem itself an offence would go too far. It would convert protocol to obligation, and it would over-penalise political dissent or social non-conformity. Much better in a National Anthem Bill to provide merely what those listening to it “should” do, and permit the general law on public order to deal with disturbances to the singing of the anthem. People like Tommie Smith, John Carlos, Mahmoud Abdul-Rauf and Colin Kaepernick should be able to make their protests during the anthem, even if politicians like Barack Obmama and Jeremy Corbyn are criticised for their singing voices.

So, we should be able to debate whether the GAA should continue to play the national anthem before matches, and the likes of Rory McIlroy or Conor McGregor should be able to make a point about or with it, and it shouldn’t matter if a Taoiseach sings the anthem or not, without running foul of a National Anthem Bill.