1. Introduction

1. Introduction

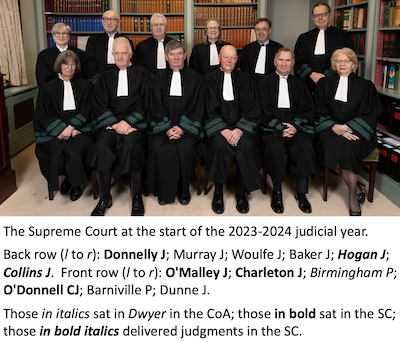

The Supreme Court has dismissed Graham Dwyer’s appeal against his conviction for the murder of childcare worker Elaine O’Hara (BBC | Examiner | Irish Independent | Irish Times | Gazette.ie | RTÉ | Sky | TheJournal.ie). The Court held that evidence of mobile phone traffic and location data was admissible at his trial. Collins J (pictured back right, in the photograph on the left) (O’Donnell CJ; Dunne, Charleton, O’Malley and Donnelly JJ concurring) delivered the judgment of the Court; Hogan J (pictured beside Collins J) concurred in a short judgment. In this post I want to sketch the background to the decision, the decision itself, and some consequences. In a series of forthcoming posts, I will look at all of those issues in more detail.

2. Background

On 27 March 2015, following a lengthy and high-profile trial in the Central Criminal Court before Hunt J and a jury, Dwyer was convicted of the murder of Elaine O’Hara in August 2012. He was subsequently sentenced to imprisonment for life, and he continues to serve that sentence.

Since January 2008, there had been an intense sexual relationship between him and Elaine O’Hara; and, after March 2011, they had communicated with each other by prepaid mobile phones. Traffic and location data relating to those phones, to Dwyer’s work phone, and to other phones, was relied upon by the prosecution at trial. The data had been retained and accessed pursuant to the Communications (Retention of Data) Act 2011 (the 2011 Act), which had given effect to the Data Retention Directive (Directive 2006/24/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 15 March 2006 on the retention of data generated or processed in connection with the provision of publicly available electronic communications services or of public communications networks and amending Directive 2002/58/EC (OJ L 105, 13.4.2006, pp54–63)) (the Directive). Section 3 of the 2011 Act required telecommunication service providers to retain traffic and location data, in some cases for one year, in others for two; and section 6(1)(a) provided that

A member of the Garda Síochána not below the rank of chief superintendent may request a service provider to disclose to that member data retained by the service provider in accordance with section 3 where that member is satisfied that the data are required for—

(a) the prevention, detection, investigation or prosecution of a serious offence, …

In Joined Cases C-293/12 and C-594/12 Digital Rights Ireland Ltd v Minister for Communications, Marine and Natural Resources and Kärntner Landesregierung (ECLI:EU:C:2014:238; CJEU, Grand Chamber; 8 April 2014) [DRI] the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) struck down the Directive as a disproportionate infringement of the rights to privacy and the protection of personal data in Articles 7 and 8 of the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the EU (CFR EU). In Joined Cases C-203/15 and C-698/15 Tele2 Sverige AB v Post- och telestyrelsen and Secretary of State for the Home Department v Tom Watson (ECLI:EU:C:2016:970; CJEU, Grand Chamber; 21 December 2016) [Tele 2], the CJEU explained that, as a consequence of DRI, EU law (i) precludes national legislation which, for the purpose of fighting crime, provides for “general and indiscriminate” retention of traffic and location data, and (ii) requires safeguards in any more targeted retention regime.

Having regard to DRI and Tele 2, Dwyer argued that the “general and indiscriminate” retention of data pursuant to section 3 and of access to such data pursuant to section 6(1)(a) of the 2011 Act were disproportionate infringements of his privacy rights, and that evidence accessed on foot of section 6(1)(a) should not have been admitted. At trial, Hunt J had held (i) that the evidence had not been gathered illegally, but (ii) that, if it had been, he had a discretion to admit it, which he exercised in favour of its admission. After his conviction, Dwyer therefore commenced two actions, a plenary action to establish the invalidity of the Act, and a criminal appeal against his conviction.

In the pleanary proceedings [Dwyer (No 1)], in Dwyer v Commissioner of An Garda Siochana [2018] IEHC 685 (06 December 2018) O’Connor J in the High Court held that section 6(1) of the 2011 Act “contravene[d] EU law …” ([3.107]). He subsequently made a declaration that section 6(1)(a) of the 2011 Act, insofar as it relates to data “retained on a general and indiscriminate basis” was inconsistent with EU law ([2019] IEHC 48 (11 January 2019) [10]). The Supreme Court granted leave for a direct appeal ([2019] IESCDET 108 (28 May 2019)), and referred several questions to the CJEU, concerning the validity of section 6(1)(a), the possibility of limiting the temporal effects of any decision striking that section down, and the admissibility of data accessed under it (Clarke CJ; O’Donnell, McKechnie, MacMenamin, O’Malley and Irvine JJ concurring; Charleton J dissenting).

In Case C-140/20 GD v Commissioner of An Garda Síochána (ECLI:EU:C:2022:258; CJEU, Grand Chamber; 5 April 2022) [GD], the CJEU reaffirmed that EU law (i) precludes national legislation which, for the purpose of fighting crime, provides for “general and indiscriminate” retention of traffic and location data, and (ii) permits a more targeted regime for the purposes of safeguarding national security, combating serious crime and preventing serious threats to public security, provided that those measures are subject to substantive and procedural safeguards. The CJEU also held that (iii) EU law precludes a national court from limiting the temporal effects of a declaration of invalidity, and that (iv) questions of admissibility of evidence are a matter for national law. When the matter returned to the Supreme Court, the Court simply affirmed O’Connor J’s declaration and dismissed the appeal. Soon thereafter, the Oireachtas passed the Communications (Retention of Data) (Amendment) Act 2022 (noted here and here) to fill the gap created by the invalidity of section 6(1)(a). The obligation to retain data in section 3 of the 2011 Act was reformulated and limited to a year by section 3 of the 2022 Act; and the right to access such data in section 6 of the 2011 Act was entirely restated by section 5 of the 2022 Act.

In any event, armed with that declaration, Dwyer commenced his criminal appeal [Dwyer (No 2)]. In Director of Public Prosecutions v Dwyer [2023] IECA 70 (24 March 2023) (Birmingham P; Edwards and Kennedy JJ) dismissed the appeal. The Court held that

- the traffic and location evidence in controversy was not very significant at all ([116]);

- the Gardaí were blameless in the manner in which they had conducted the investigation ([124]);

- the decision of the CJEU in GD put beyond doubt that, having regard to the CFR EU ([128]), illegality attached to the retention of the data which was accessed by Gardaí ([126)]);

- this case concerned a breach of a provision of a Directive read in light of the CFR EU ([129]), and should therefore be treated as a case of illegally but not unconstitutionally obtained evidence ([130]);

- having regard to the decision of the Supreme Court in People (AG) v O’Brien [1965] IR 142 ([130]) – (by which it is a matter of discretion for the trial judge to decide, in all the circumstances of the case, whether or not to admit such evidence ([1965] IR 142, 160 (Kingsmill Moore J; Lavery and Budd JJ concurring; O Dálaigh and Walsh JJ delivered separate judgments) [O’Brien]) – evidence normally should not be excluded ([131)];

- Hunt J at trial had exercised that discretion to admit the evidence;

- “a contrary ruling would … be wrong to the point of absurdity and would bring the administration of the law into well-deserved contempt”; (citing People (AG) v O’Brien [1965] IR 142 (Lavery J));

- if the evidence was not merely illegally obtained, but unconstitutionally obtained, then having regard to the decision of the Supreme Court in People (DPP) v JC [2017] 1 IR 417, [2015] IESC 31 (15 April 2015) – (where evidence is unconstitutionally obtained, but not consciously and deliberately in violation of constitutional rights, there is a presumption against the admissibility of the evidence; but it should be admitted if it was obtained where any breach of rights was due to inadvertence or derives from subsequent legal developments ([5.20], [7.2(iv)] (Clarke J; Denham CJ and O’Donnell and MacMenamin JJ concurring) [JC]) – the evidence would still be admissible ([137]); and

- having regard to section 3(1) of the Criminal Procedure Act, 1993 (the 1993 Act) [the proviso], even if the evidence were inadmissible, no miscarriage of justice had actually occurred ([141]).

For these reasons, the Court of Appeal dismissed the appeal. The Supreme Court granted leave to appeal ([2023] IESCDET 88 (04 July 2023)). In the view of the panel (O’Donnell CJ, Collins and Donnelly JJ) ([19]-[20]):

… significant issues of general public importance arise as to admissibility of CDR [call data records] evidence retained and accessed under the 2011 Act in light of the CJEU’s decision in GD. These issues include the question of whether the admissibility of such evidence is governed by O’ Brien, by JC or by some other test and how that test is to be applied in the circumstances here, where the CDR evidence was obtained in compliance with the provisions of the 2011 Act but where that Act was subsequently found to be inconsistent with EU law. The proper characterisation of the illegality involved is also a matter of general public importance.

The Court is also satisfied that the issue regarding the scope and application of section 3(1) of the Criminal Procedure Act, 1993 is one of general public importance.

The appeal was heard on 16 January 2024, and the Court gave judgment today.

3. The decision of the Supreme Court

Today, in Director of Public Prosecutions v Dwyer [2024] IESC 39 (31 July 2024) Collins J gave the judgment of the Court. O’Donnell CJ, and Dunne, Charleton, O’Malley and Donnelly J concurred. Hogan J concurred in a short judgment.

Collins J began by noting that the main traffic and location evidence against Dwyer related to his work phone, and that the appeal was concerned solely with the admissibility of the data relating to that phone ([14]). He clarified that the appeal raised two issues: (i) whether the Trial Judge had erred in admitting the disputed traffic and location data into evidence (the admissibility issue), and, if so (2) whether the Court of Appeal erred in concluding, even if the evidence ought not to have been admitted, the Appellant’s conviction should nonetheless be affirmed pursuant to section 3(1) of the Criminal Procedure Act, 1993 [the proviso], on the grounds that “no miscarriage of justice [had] actually occurred” (the proviso issue).

As to the admissibility issue, at the time of hearing of the appeal in this case, the Court had heard two appeals raising materially identical admissibility issues, and had subsequently given judgment (People (DPP) v Smyth [2024] IESC 22 (17 June 2024) (Collins J) (O’Donnell CJ, Barniville P, and Dunne, Charleton and O’Malley JJ concurring) (Hogan J (dissenting) [Smyth]); DPP v McAreavey [2024] IESC 23 (17 June 2024) (Collins J) (O’Donnell CJ, Barniville P, and Dunne, Charleton and O’Malley JJ concurring); Hogan J (dissenting) [McAreavey]).The Court held that traffic and location data at issue in those cases had been correctly admitted in evidence by the Special Criminal Court. Collins J ([32]) described the outcome of those cases as follows:

- the traffic and location data at issue had to be regarded as having been retained and accessed in breach of the CFR EU;

- the admissibility of that evidence fell to be assessed by reference to JC;

- the breach of the CFR EU was not “deliberate and conscious” in the sense used in JC;

- rather the breach arose as a result of a ‘subsequent legal development’; namely the combined effect of the CJEU’s judgment in GD and the declaration subsequently granted by the Supreme Court in Dwyer (No 1); so that

- in the circumstances, the traffic and location data at issue there was admissible under JC; and

- no exception to JC [such as the “general considerations of fairness” discussed in People (DPP) v Quirke (No 2) [2023] 1 ILRM 445, [2023] IESC 20 (28 July 2023)] applied, because the traffic and location data at issue could have been retained in a manner compatible with the Charter [(38)].

The same considerations applied to admit the traffic and location data at issue in this case. Collins J highlighted that (emphasis added):

42. … the exclusionary rule formulated in JC is not an absolute rule of exclusion. It does not follow from the fact that evidence has been obtained in circumstances of unconstitutionality (or in breach of the Charter [CFR EU]) that it must be excluded. The issue of admissibility of evidence is a distinct issue, following on from but also distinct from the issue of the lawfulness of the circumstances in which the evidence was obtained. That issue – admissibility – engages compelling interests above and beyond the interests of the accused. … JC seeks to balance those interests and does so in a way that does not require the exclusion of unconstitutionally obtained evidence in all or nearly all cases. For the reasons set out in the majority judgment in JC, any absolute rule of exclusion exacts too high a price in terms of the adverse impact on the administration of criminal justice.

44. As the CJEU made clear in GD, … the admissibility of the disputed traffic and location data was and is a matter of Irish law, subject to the principles of effectiveness and equivalence. For the reasons set out in Smyth, the question of admissibility is governed by JC. The Appellant accepts that the JC test satisfies the principles of equivalence and effectiveness: it was on that basis that he contended that JC was applicable to evidence obtained in breach of the Charter. Admissibility is not governed by EU law, whether the provisions of the Charter or otherwise. As already explained, the application of the JC test here leads to the conclusion that the evidence was admissible, notwithstanding that it was obtained in breach of the Charter [CFR EU].

On the admissibility issue, therefore, he concluded ([46]) that, as was evident from his judgment in Smyth, he accepted many of the submissions that had been advanced on Mr Dwyer’s behalf. In particular, he accepted that the evidence at issue here was obtained in breach of the CFR EU, and that issue of admissibility fell to be determined by JC. However, applying that case, he held that the traffic and location data evidence was properly admitted at trial.

As to the proviso issue, Collins J provided a comprehensive analysis of the operation of section 6 of the 1993 Act. Building on the decision of O’Malley J (MacMenamin, Dunne, Charleton and Woulfe JJ concurring) in People (DPP) v Sheehan [2021] 1 IR 33, [2021] IESC 49 (29 July 2021) he held that, even if the traffic and location data relating had been inadmissible

97. … the remaining evidence available to the prosecution was more than sufficient to establish attribution beyond any reasonable doubt. The evidence was in fact overwhelming and unanswerable. …

98. It follows … that there was … no “miscarriage of justice” within the meaning of the proviso …

Hogan J delivered a short conurring judgment. He considered that the question presented here was essentially determined by Smyth and McAreavey ([3]), in which he had dissented. Nevertheless, he deferred here to the majority in Smyth ([4]). In Mogul of Ireland Ltd v Tipperary (NR) County Council [1976] IR 260, 272, Henchy J held that a decision of the full Supreme Court “given in a fully argued case on a consideration of all the relevant materials, should not normally be overruled merely because a later Court inclines to a different conclusion”. Whilst the doctrine of precedent should not be applied so rigorously in constitutional cases ([11]), nevertheless, since Smyth was fully argued and judgments was delivered following consideration of all of the relevant materials ([10]-[11]), he considered that it would be “importunate” of him here to insist on adhering to to his dissent in Smyth. Hence, he treated the majority decision in Smyth as binding ([15]), and he followed it, “if only for reasons of stare decisis” ([17]).

4. Consequences

On the proviso issue, Collins J has provided a thorough analysis of its operation. On the admissibility issue, the applicable legal principles had mostly been decided in Smyth and McAreavey, and the Court’s judgment today simply applied the principles from those cases. But those principles are important because they are substantially different from the decision of the Court of Appeal in this case. The most significant difference lies in the fact that the Court of Appeal considered that evidence obtained in breach of a Directive, read in the light of the CFR EU, had been illegally obtained, so that (pursuant to O’Brien) the trial judge had a discretion to admit it. On the other hand, the Supreme Court held that the evidence had been obtained in breach of the CFR EU, and that questions of admissibility fell to be considered on the basis of the test in JC, which the Court applies to evidence obtained in breach of constitutional rights. However, even on this stricter test, having regard to Smyth and McAreavey, the Court was satisfied that the evidence was properly admitted.

As the CJEU had explained in GD, the admissibility of evidence obtained by means of invalid retention is, “in accordance with the principle of procedural autonomy of the Member States, a matter for national law, subject to compliance, inter alia, with the principles of equivalence and effectiveness” ([127]-[128]). Here, Dwyer accepted ([44]; see the emphasis supplied in the extract above) that the JC test satisfies the principles of equivalence and effectiveness. The latter principle, in particular, requires that national rules do not make it excessively difficult or impossible in practice to exercise rights conferred by EU law (Case C-289/21 IG v Varhoven administrativen sad (ECLI:EU:C:2022:920; CJEU, Fifth Chamber; 24 November 2022) [33]), and that the full effectiveness of EU law requires the effective protection of the rights which individuals derive from EU law (ibid [35]). It would have been interesting to explore whether these principles require a stricter test of admissibility of evidence obtained in breach of EU law (indeed, there might have been material here for a further reference to the CJEU). From at least 1990 (since The People (DPP) v Kenny [1990] 2 IR 110, [1990] ILRM 569, if not before; see the judgments of Walsh J in O’Brien (1965) (above) and The People v Shaw [1982] IR 1 (SC)) until 2015 (when JC overruled Kenny) Irish law considered that evidence obtained in “deliberate and conscious” violation of constitutional rights had to be excluded unless there were “extraordinary excusing circumstances” to justify its admissibility. Had that or a similar test been applicable for reasons of the effectiveness of EU law, it would then have been interesting to see if the Court had found “extraordinary excusing circumstances” here.

In any event, Collins J’s judgments in Smyth and McAreavey and today in Dwyer (No 2) are careful and subtle, and I will tease out their consequences in a series of forthcoming posts.

A second difference is that the provisions of the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR) were considered by O’Connor J in Dwyer (No 1), but not in the Court of Appeal or in the Supreme Court in Dwyer (No 2). O’Connor J held that question of whether or not a general and indiscriminate retention regime is compatible with the ECHR “remains undetermined” ([3.76]). However, since the decision of O’Connor J, the European Court of Human Rights has handed down an important decision on that very issue in Pietrzak & Bychawska-Siniarska v Poland 72038/17 & 25237/18, [2024] ECHR 464 (28 May 2024). It held, inter alia, that Polish legislation, which required general and indiscriminate retention for possible future use by the relevant national authorities, was not necessary in a democratic society, and thus infringed the ECHR. It may be, therefore, that Dwyer might apply to the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) on this issue. However, even if he is successful, it will not be sufficient for him to win his freedom in Ireland. On the one hand, he may consider this not worth the candle. On the other, he might consider that, having come this far, he may as well take one more step. Time will tell.

For the present, it is sufficient that the Court dismissed Dwyer’s appeal. More than nine years after his conviction on 27 March 2015, his epic challenge in the domestic courts to the admissibility of traffic and location data at his trial is finally over. He has lost. Even if he applies to there ECtHR, he will now serve out the remainder of his life sentence for the murder of Elaine O’Hara. May she rest in peace.

Thanks for this excellent analysts.

You’re very welcome. Glad it’s helpful. Check back again for more detail in my next few posts.

Excellent. Thank you Eoin. Always an interesting topic.

You’re very welcome, Darach. Glad it’s helpful. Check back again for more detail in my next few posts (which will be interspersed with some defamation material, given that the new Bill has also just dropped. Like busses, you wait ages for interesting developments, and then two come along at once!