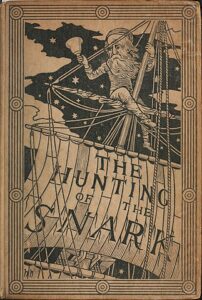

The Hunting of the Snark is a nonsense poem written by Lewis Carroll subtitled An Agony in 8 Fits. In Fit 6, the Barrister dreams that the eponymous Snark serves as counsel for the defence, finds the verdict as the jury, and passes sentence as the judge. Perhaps it is fitting then to observe that, by way of update to yesterday’s post about Bofinger v Kingsway Group Limited (2009) 239 CLR 269, [2009] HCA 44 (13 October 2009), Legal Eagle on SkepticLawyer characterises the judgment as “yet another snark at unjust enrichment”. True, but reaffirming a light approach to the “unifying legal concept” of unjust enrichment is not necessarily a bad thing, even if the tone is indeed unnecessarily snarky. She does concede that, “to give the High Court credit where credit is due, it gives reasoned arguments for rejecting the Banque Financière decision (see Banque Financière de la Cité v Parc (Battersea) Ltd [1999] 1 AC 221; [1998] UKHL 7 (26 February 1998)). It would sound quite reasonable if it weren’t for the usual snark beforehand” (given my views in my earlier post, it’s no surprise that I agree with her here). Her snark is that the Court does not provide similarly reasoned arguments for what she sees as negative knee-jerk responses to unjust enrichment reasoning. Among the questions she says the Court is ducking:

The Hunting of the Snark is a nonsense poem written by Lewis Carroll subtitled An Agony in 8 Fits. In Fit 6, the Barrister dreams that the eponymous Snark serves as counsel for the defence, finds the verdict as the jury, and passes sentence as the judge. Perhaps it is fitting then to observe that, by way of update to yesterday’s post about Bofinger v Kingsway Group Limited (2009) 239 CLR 269, [2009] HCA 44 (13 October 2009), Legal Eagle on SkepticLawyer characterises the judgment as “yet another snark at unjust enrichment”. True, but reaffirming a light approach to the “unifying legal concept” of unjust enrichment is not necessarily a bad thing, even if the tone is indeed unnecessarily snarky. She does concede that, “to give the High Court credit where credit is due, it gives reasoned arguments for rejecting the Banque Financière decision (see Banque Financière de la Cité v Parc (Battersea) Ltd [1999] 1 AC 221; [1998] UKHL 7 (26 February 1998)). It would sound quite reasonable if it weren’t for the usual snark beforehand” (given my views in my earlier post, it’s no surprise that I agree with her here). Her snark is that the Court does not provide similarly reasoned arguments for what she sees as negative knee-jerk responses to unjust enrichment reasoning. Among the questions she says the Court is ducking:

Are there benefits to having a unified concept of unjust enrichment? Are there detriments? Are all restitution scholars necessarily indulging in “top-down reasoning”? Is top-down reasoning necessarily a bad thing? Should the law evolve? I mean, they’re the High Court — within reason, the law is what they say it is. Why have the English courts made the changes they have? How have these changes worked? Have they made private law more manageable or less? I don’t mind so much what position the High Court takes on these questions as long as it actually thinks about it rather than just snarks. … I really wish the High Court would either (a) engage in reasoned criticism of unjust enrichment scholars or (b) desist from snarking.

I must say that I didn’t read the unjust enrichment comments quite as negatively as Legal Eagle did. At para 86, the Court pointed out that the seminal case of David Securities Pty Ltd v Commonwealth Bank of Australia (1992) 175 CLR 353, 378-379; [1992] HCA 48 [45] (7 October 1992), confined the “unifying legal concept” of unjust enrichment to a descriptive but not prescriptive role, and therefore rejected the view that it was “a definitive legal principle according to its own terms”. This is what they had already held in Pavey & Matthews Pty Ltd v Paul (1987) 162 CLR 221; [1987] HCA 5 (4 March 1987). The concept provides a means for comparing and contrasting various categories of liability, and assists in the determination by the ordinary processes of legal reasoning of the recognition of obligations in a new or developing category of case, but it is not a self-executing principle (such as applies in Canada after Pettkus v Becker [1980] 2 SCR 834; 1980 CanLII 22 (18 December 1980); see most recently Ermineskin Indian Band and Nation v Canada [2009] 1 SCR 222; 2009 SCC 9 (13 February 2009)). Of course, cases like Roxborough v Rothmans of Pall Mall Australia Ltd (2001) 208 CLR 516; [2001] HCA 68 (6 December 2001), Farah Constructions Pty Ltd v Say-Dee Pty Ltd (2007) 230 CLR 89; [2007] HCA 22 (24 May 2007) and Lumbers v W Cook Builders Pty Ltd (In liq) (2008) 232 CLR 635; [2008] HCA 27 (18 June 2008) resisted transmuting the unifying but descriptive legal concept into a prescriptive and self-executing principle – and, yes, they did so snarkily – but they did not undercut the essential analytical foundations of Australia’s law of restitution for unjust enrichment. Indeed, the position greatly resembles the approach taken in Ireland (after the Bricklayers’ Hall case [1996] 2 IR 468, 483; [1996] 2 ILRM 547, 558, (24 July 1996) [37]-[40] (doc | pdf | html) (Keane J; Hamilton CJ, O’Flaherty, Blayney and Barrington JJ concurring)) and in the UK (after Kleinwort Benson Ltd v Lincoln City Council [1999] 2 AC 349, [1998] UKHL 38 (29 October 1998); indeed, it was the approach to restitution which Lord Hoffmann in Banque Financière applied to subrogation!).

Bofinger v Kingsway simply reaffirms this general Australian approach. I agree that the tone of the decision is snarky, and it does take a few gratuitous swipes at some of Peter Birks‘s later arguments. But the House of Lords in Deutsche Morgan Grenfell Group Plc v Inland Revenue & Anor [2007] 1 AC 558], [2006] UKHL 49 (25 October 2006) was not particularly receptive to them either. What all this demonstrates, I think, is that there are intellectually respectable arguments in favour of the position articulated by the High Court. Nevertheless, I take Legal Eagle’s point that the Court should articulate them a little more clearly, and with less snarkiness.

Finally, on another issue, I also agree with her that the Court (distracted, I think, by its jurisprudence relating to the remedial constructive trust) insufficiently differentiated between a proprietary constructive trust and a personal liability to account as a constructive trustee. Millett LJ described the difference in Paragon Finance Plc v D B Thakerar & Co (A Firm) [1998] EWCA Civ 1249 (21 July 1998):

Regrettably, however, the expressions “constructive trust” and “constructive trustee” have been used by equity lawyers to describe two entirely different situations. The first covers those cases … where the defendant, though not expressly appointed as trustee, has assumed the duties of a trustee by a lawful transaction which was independent of and preceded the breach of trust and is not impeached by the plaintiff … In the first class of case, however, the constructive trustee really is a trustee. … In these cases the plaintiff does not impugn the transaction by which the defendant obtained control of the property. He alleges that the circumstances in which the defendant obtained control make it unconscionable for him thereafter to assert a beneficial interest in the property.

The second class of case is different. It arises when the defendant is implicated in a fraud. Equity has always given relief against fraud by making any person sufficiently implicated in the fraud accountable in equity. In such a case he is traditionally though I think unfortunately described as a constructive trustee and said to be “liable to account as constructive trustee.” Such a person is not in fact a trustee at all, even though he may be liable to account as if he were. He never assumes the position of a trustee, and if he receives the trust property at all it is adversely to the plaintiff by an unlawful transaction which is impugned by the plaintiff. In such a case the expressions “constructive trust” and “constructive trustee” are misleading, for there is no trust and usually no possibility of a proprietary remedy; they are “nothing more than a formula for equitable relief” …

I’m not a restitution zealot – I do think that it has been held up as the solution to some private law problems when it isn’t. Thus I take the High Court’s point that it doesn’t actually solve anything in a subrogation context. Why bother if it doesn’t make the solution easier?

On the other hand, the constructive trust analysis is deeply unsatisfactory. I’m surprised that they didn’t use that passage by Millett LJ which you excerpt above – that would be the perfect explanation.

What annoys me about the Australian High Court is that according to them, there is no action in unjust enrichment – you have to institute an action for money had and received or a quantum meruit or whatever. I fail to see why we should be bound by these ancient, idiosyncratic forms of action.

I think much of the Australian judicial negativity about unjust enrichment comes from badly pleaded cases. There was a time when litigants would just stick, “The defendant’s conduct was unconscionable” at the end of a pleading without particulars as a kind of sloppy “catch-all”. Now “the defendant has been unjustly enriched” has replaced this as a catch-all. But this does not mean we should throw out unjust enrichment altogether. It means we should educate lawyers on how to plead it.

And yes, I did snark back at the High Court – their tone got my goat! :-P