The title of this post is taken from the third paragraph of Milton’s Areopagitica. As I commented in an earlier post, one of the classic liberal justifications for freedom of expression was stated by John Milton (pitctured left) in his Areopagitica – A Speech for the Liberty of Unlicenc’d Printing, to the Parlament of England. According to The Writer’s Almanac with Garrison Keillor (with added links):

The title of this post is taken from the third paragraph of Milton’s Areopagitica. As I commented in an earlier post, one of the classic liberal justifications for freedom of expression was stated by John Milton (pitctured left) in his Areopagitica – A Speech for the Liberty of Unlicenc’d Printing, to the Parlament of England. According to The Writer’s Almanac with Garrison Keillor (with added links):

It was on this day in 1644 that John Milton published a pamphlet called Areopagitica, arguing for freedom from censorship. He said,

I wrote my Areopagitica in order to deliver the press from the restraints with which it was encumbered; that the power of determining what was true and what was false, what ought to be published and what to be suppressed, might no longer be entrusted to a few illiterate and illiberal individuals, who refused their sanction to any work which contained views or sentiments at all above the level of vulgar superstition.

He compared the censoring of books to the Spanish Inquisition and claimed that the government wanted “to bring a famine upon our minds again.”

Milton was not just championing this cause out of the goodness of his heart — he had a far more personal reason. Many years earlier, his father had lent £300 and a £500 bond to a man named Richard Powell. In the early summer of 1642, John Milton traveled to Oxfordshire, where Powell lived, and one month later he returned to London with a 17-year-old bride, Powell’s daughter. But the marriage didn’t work out very well — according to contemporary biographers, Mary found Milton dull and severe compared to her generous and warm family. In any case, after a month, she went home to visit her relatives and then refused to come back (she did, years later). He was not allowed to divorce her and find a new wife because the only grounds for divorce were adultery.

In 1643, he published a pamphlet called Doctrine and Discipline of Divorce. He argued that marriage should be mutually supportive. He deconstructed biblical texts and civil and canon law. He wrote:

Marriage is a cov’nant the very beeing wherof consists, not in a forc’t cohabitation, and counterfet performance of duties, but in unfained love and peace. […] It is a lesse breach of wedlock to part with wise and quiet consent betimes, then still to soile and profane that mystery of joy and union with a polluting sadnes and perpetuall distemper; for it is not the outward continuing of mariage that keeps whole that cov’nant, but whosoever does most according to peace and love, whether in mariage, or in divorce, he it is that breaks mariage least; it being so often written, that Love only is the fulfilling of every Commandment.

Milton followed up Doctrine and Discipline of Divorce with two more pamphlets about divorce. He refused to get any of them approved and licensed by the government before printing, which had been mandated in an order from 1643. His divorce pieces got a lot of negative response, in many cases from people who thought his ideas were immoral and blasphemous, but more specifically from people who were shocked that he was publishing such controversial material and not getting it licensed first. So it was in reaction to all the uproar that he wrote Areopagitica. He wrote,

Who kills a man kills a reasonable creature, God’s image; but he who destroys a good book, kills reason itself, kills the image of God, as it were in the eye.

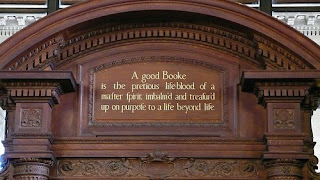

The Licensing Order 1643 required that all publications receive a pre-publication licence, and that all printing materials with the names of author, printer and publisher be entered in the Register at Stationers’ Hall. The Stationers’ Company was given the responsibility of acting as censor, in return for a monopoly of the printing trade. In Areopagitica (title page, left), Milton articulated the classic argument against prior restraint, on the grounds that it amounted to little more than an excuse for state control of thought. However, this plea to rescind the 1643 order fell on deaf ears, though the order eventually was allowed to lapse in 1694. Although the context has long since fallen away, Milton’s Areopagitica still stands as a monument against censorship that continues to resonate today. It directly influenced John Stuart Mill‘s On Liberty, and the still-controversial formative US Supreme Court judgments of Justice Holmes. Finally, over a door in the New York Public Library, there is an inscription from the paragraph of Areopagitica from which the title to this post is taken:

The Licensing Order 1643 required that all publications receive a pre-publication licence, and that all printing materials with the names of author, printer and publisher be entered in the Register at Stationers’ Hall. The Stationers’ Company was given the responsibility of acting as censor, in return for a monopoly of the printing trade. In Areopagitica (title page, left), Milton articulated the classic argument against prior restraint, on the grounds that it amounted to little more than an excuse for state control of thought. However, this plea to rescind the 1643 order fell on deaf ears, though the order eventually was allowed to lapse in 1694. Although the context has long since fallen away, Milton’s Areopagitica still stands as a monument against censorship that continues to resonate today. It directly influenced John Stuart Mill‘s On Liberty, and the still-controversial formative US Supreme Court judgments of Justice Holmes. Finally, over a door in the New York Public Library, there is an inscription from the paragraph of Areopagitica from which the title to this post is taken:

|

A good book is the precious lifeblood of a master spirit, embalmed and treasured up on purpose to a life beyond life.

5 Reply to “A good book is the precious lifeblood of a master spirit”