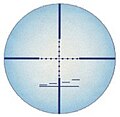

In the aftermath of the attempted assassination of Representative Gabrielle Giffords and the murder of six other people in Arizona last week, a fierce debate has broken out over the heated political rhetoric – often coarse, martial, and vitriolic – that is now distressingly commonplace in US political discourse. The specific background is a map which appeared on Sarah Palin‘s website targeting the seats of political opponents – including Rep. Giffords – in rifle-sight cross-hairs, and which has therefore focussed signficant attention on Palin’s confused response to the tragedy. Of course, politicians and pundits across the political spectrum have used such language and imagery, and the issues of principle arise in the context of the general standard of debate rather than in the context of any particular politician, pundit or party. I want in this post to set out some of the general free speech arguments that I have come across since Saturday.

In the aftermath of the attempted assassination of Representative Gabrielle Giffords and the murder of six other people in Arizona last week, a fierce debate has broken out over the heated political rhetoric – often coarse, martial, and vitriolic – that is now distressingly commonplace in US political discourse. The specific background is a map which appeared on Sarah Palin‘s website targeting the seats of political opponents – including Rep. Giffords – in rifle-sight cross-hairs, and which has therefore focussed signficant attention on Palin’s confused response to the tragedy. Of course, politicians and pundits across the political spectrum have used such language and imagery, and the issues of principle arise in the context of the general standard of debate rather than in the context of any particular politician, pundit or party. I want in this post to set out some of the general free speech arguments that I have come across since Saturday.

First, Jack Shafer in Slate:

In Defense of Inflamed Rhetoric

The awesome stupidity of the calls to tamp down political speech in the wake of the Giffords shooting.

… For as long as I’ve been alive, crosshairs and bull’s-eyes have been an accepted part of the graphical lexicon when it comes to political debates. Such “inflammatory” words as targeting, attacking, destroying, blasting, crushing, burying, knee-capping, and others have similarly guided political thought and action. Not once have the use of these images or words tempted me or anybody else I know to kill. … Asking us to forever hold our tongues lest we awake their deeper demons infantilizes and neuters us and makes politicians no safer.

Brian J. Buchanan makes much the same point at the First Amendment Center’s site: Free speech not on trial in Giffords shooting; and Bruce Gorton on Times Live suggests – rather naively, I fear – the public should simply stop listening to the pundits or voting for the politicians who use such extreme militaristic langauge, rather than censoring them. With rather more nuance, on the NYT’s Opinionator blog, David Brooks and Gail Collins consider whether moderation (in political language) is possible or desirable in these kinds of circumstances.

Second, Rahul Mahajan on Empire Notes replied to Shafer:

Of Free Speech, Bullseyes, Gabrielle Giffords, and Sarah Palin

… The question is whether this is speech protected by the First Amendment or incitement to commit violence, which in certain rather specific circumstances is not protected. … Jack Shafer … just posted a column saying that all such claims are “awesomely stupid,” …

Now, I think Shafer’s article is asinine … I’m not a free speech absolutist, in part because frankly any absolutism is rationally suspect. In particular, free speech absolutism would have to argue that freedom of speech always and inevitably must trump every other concern, rights-based or not, and I don’t see how one could argue this. It’s worth noting that, for example, Milton’s celebrated defense of freedom of speech and the press in Areopagitica [see here] is not an absolute one. It accepts that public welfare is the ultimate criterion and, in particular, argues that it’s ok to censor certain publications — what is argues against is prior restraint. …

… It’s not hard to come up with examples of speech which should not be protected … [such as] Holmes’ famous example of shouting fire in a crowded theater [see here and here], but they also make it clear that incitement does not require explicit advocacy. … And then there are Shafer’s examples of the kind of violent language we use every day, which, he points out, he uses too. There is a big difference to be considered, however. Shafer is relentlessly rational, never suggests that people should be ready to commit violence, and never tries to foster paranoia in other people. Compare this to the sickening vomitous mass of radical right rhetoric in this country. If Shafer regularly told a bunch of people on the border of paranoia that everything is out to get them, if he exhorted them to carry guns to political rallies, if he told them to be ready for “Second Amendment solutions” to their problems, if he was leading a growing number of people to reclaim the idea of the right of revolution (armed), then his use of violent language would look different. …

Third, the counter-case is made by Aryeh Neier on the Index on Censorship Blog:

Giffords shooting: Free speech in the crosshairs

Calls to outlaw violent political rhetoric in the wake of the Tucson attack are misguided, says Aryeh Neier. The solution is not to ban vitriol but to speak out against it

… Just banning use of the particular images such as those that appeared on Sarah Palin’s website would probably do little good. … If an attempt were made to use the law to prohibit any expression that might have an effect on [the man arrested and charged in connection with the massacre], it could only be done through legislation that gives law enforcement authorities broad power. … Of course, American constitutional law allows nothing of the sort. … A specific threat of violence against a specific person can be made a crime. It can also be a crime to incite violence in circumstances when there is an imminent threat that violence will take place. Beyond that, however, American commitment to the freedoms guaranteed by the First Amendment does not permit sanctions.

There are also good reasons in public policy not to permit broader law enforcement powers. Experience elsewhere indicates that such powers are mainly used by officials as a means of punishing political dissenters. Where expression is concerned, it is essential that the state should have as little discretion as possible when to use the power of the law. Because expression can take and does take so many different forms, providing the authorities with broad discretion is particularly subject to abuse.

If criminal sanctions are not the … [remedy], is there an alternative? Probably the only one is the traditional remedy for bad speech: more speech. … We cannot and should not use the law to stop irresponsible politicians like Sarah Palin from expressing their views even when those views could influence a deranged person who has ready access to dangerous weapons. But we should make clear our contempt for those views.

Finally, Adam Wagner on the UK Human Rights blog considers the detail of the restrictions allowed by the law in such circumstances in the US and in Europe:

Shooting of Congresswoman Giffords and the limits of free speech

… What is to be done about violent “rage”, publicly expressed? Political rhetoric in the United States is often more offensive and charged than in the UK, due in part to the more robust freedom of expression protections under the US Constitution. Under English law, freedom of expression is protected under Article 10 of the European Convention.

However, Article 10 is subject to a number of qualifications, including the interests of national security, territorial integrity, public safety, the prevention of disorder or crime, the protection of health or morals, and the protection of the reputation or rights of others.

For example, political expression is restricted by criminal laws against hate speech. … By contrast, … [a]lthough the United States does have laws against hate speech, … [that] speech must incite imminent violence. This is difficult to prove and as such has led to few successful prosecutions.

… [On the other hand, the relevant English law] works on the assumption that such conduct can be preempted by not allowing such an atmosphere to develop in the first place.

It is, I think, quite clear that there is no direct link between any any particular politician, pundit or party and the actions of the gunman last Saturday. However, it is also quite clear that the general tenor of political debate – and not just in the US – is not merely irresponsible but often perfidious. This tragedy has brought that problem to the fore, and I don’t know if there is any easy or short term solution. Any attempt to rein that in by legislation would be doomed to fail the test set out in Brandenburg v Ohio 395 US 444 (1969):

… the constitutional guarantees of free speech and free press do not permit a State to forbid or proscribe advocacy of the use of force or of law violation except where such advocacy is directed to inciting or producing imminent lawless action and is likely to incite or produce such action.

In the European Court of Human Rights, the standard is not quite as stringent. However, in general, restrictions on incitement will be upheld as proportionate only where there is a high degree of imminence between the inciting speech and the harm sought to be prevented; and restrictions are unlikely to be upheld where effective but less restrictive alternatives are available.

The problems can’t constitutionally be solved by legislation. [Update: On the First Amendment Center blog, Ken Paulson discusses, and rejects, Rep. Robert Brady’s plans to extend an expanded version of existing legislation that criminalizes threats against the president and vice-president to ban language or symbols that could be perceived as threatening federal officials and members of Congress.] Indeed, even if the US Constitution (or the European Convention on Human Rights) didn’t prohibit a wide-ranging legislative response, it would likely be ineffective anyway. As Yvonne Daly recently argued on Human Rights in Ireland (admittedly in a different context, but in a a generally applicable argument): legislation is not always the answer, and rushing through significant legislative proposals without appropriate time for discussion is both disrespectful to the political process and reckless in terms of their impact.

The important aspect of the debate, therefore, should be how to craft responses to this tragedy which do not infringe the Brandenburg standard but which have a positive impact on the standard of US political debate. Some commentators are indeed addressing this question, but the pundits and politicians whose stock in trade is the angry tirade don’t seem to backing away from that. Each side accuses the other of double-standards; each side is frustrated at the actions and accusations of the other side; and neither side is willing to be the first to decommission their bellicose clichés. Compromise requires trust; that has completely broken down; and the mud-slinging on all sides after last weekend has only made matters worse.

In the absence of legislation, the prescription seems to be: don’t listen to them, don’t vote for them, be civil, respond in moderate language, but do respond. Somehow, in the face of anger, that doesn’t seem enough. The legal issues are clear enough, but the social and political problems seem intractable.

Update: in an excellent and balanced piece on the Guardian website, Darin Miller concludes

The Arizona shooting and the first amendment

Amid the controversy about ‘vitriolic rhetoric’, let’s remember that free speech is a foundational principle of American democracy

… We must be as willing as our founding fathers to protect the rights for which they fought. Those of the first amendment are chief among them. For unless we defend free speech from untoward attack, we risk losing it.

3 Reply to “Freedom of expression in the crosshairs”