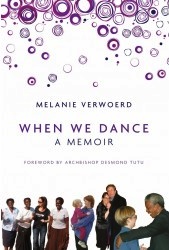

I have written before on this blog about prior restraints and temporary and permanent injunctions in defamation cases. Not long after the South African Constitutional Court effectively outlawed prior restraint in that jurisdiction (see Print Media South Africa v Minister of Home Affairs [2012] ZACC 22 (28 September 2012); blogged here), I learn that Gilligan J in the High Court in Ireland has today granted temporary injunctions to prevent the sale of a memoir written by the South African partner of a deceased celebrity Irish DJ (cover left):

I have written before on this blog about prior restraints and temporary and permanent injunctions in defamation cases. Not long after the South African Constitutional Court effectively outlawed prior restraint in that jurisdiction (see Print Media South Africa v Minister of Home Affairs [2012] ZACC 22 (28 September 2012); blogged here), I learn that Gilligan J in the High Court in Ireland has today granted temporary injunctions to prevent the sale of a memoir written by the South African partner of a deceased celebrity Irish DJ (cover left):

Gerry Ryan biography will not go sale after court challenge

Melanie’s book on Gerry Ryan pulled off shelves in court row

Melanie memoir pulled from shelves

Publication of Gerry Ryan book delayed pending court action

Publication of Verwoerd book on Ryan restrained

Verwoerd book put on hold following court hearing

Verwoerd book put on hold following court hearing

Given the parties involved, it is unsurprising that there is intense media interest in the case. However, the legal issues are interesting too. Section 33 of the Defamation Act, 2009 (also here) provides:

(1) The High Court … may, upon the application of the plaintiff, make an order prohibiting the publication or further publication of the statement in respect of which the application was made if in its opinion—

(a) the statement is defamatory, and

(b) the defendant has no defence to the action that is reasonably likely to succeed.

Paragraphs (a) and (b) set a relatively high threshold which a plaintiff has to meet before an order prohibiting publication can be made. Since subsection (3) says that “order” in sub-section (1) includes interim (s33(3)(a)) and interlocutory (s33(3)(b)) orders, then the only jurisdictional basis on which Gilligan J could have granted an interim order this morning would have been if he had been satisfied that the high threshold set by paragraphs (a) and (b) of s33(1) had been cleared. Moreover, it is clear that section 33 has to be interpreted in the light of the protections of freedom of expression by the Constitution and the European Convention on Human Rights. In particular, since such a temporary injunction constitutes a prior restraint upon speech, applications for interim or interlocutory injunctions in defamation cases must be scrutinised with particular care. To take only one example from many, in Evans v Carlyle [2008] 2 ILRM 359, [2008] IEHC 143 (08 May 2008) Hedigan J held that a court should grant an order pursuant to section 33

… warily and cautiously. It should bear in mind the importance and centrality of freedom of expression in the democratic process. The right to freedom of expression is protected both by Article 10 of the European Convention on Human Rights and by Article 40.6.1. of the Irish Constitution. The court, therefore, should be very slow to restrict, either prior to or after publication, the continuing exercise of this right.

Gilligan J declined to grant the orders sought by the plaintiff ex parte yesterday evening, insisting that the defendants be put on notice of an application this morning, when they consented to an order prohibiting publication, sale or distribution of the book until the matter comes back before the court on October 24. At that stage, to maintain the order, the plaintiff will have to establish that the high threshold set by section 33(1) has indeed been cleared, and it will be very interesting indeed to see if he succeeds in doing so.

3 Reply to “When we dance to the High Court for an injunction”