So, does Irish law now recognise a journalist source privilege?

As I wrote in my previous post, the Supreme Court in Mahon Tribunal v Keena [2009] IESC 64 (31 July 2009) (also here (pdf)) allowed the appeal against the decision of the High Court in Mahon v Keena [2007] IEHC 348 (23 October 2007). Fennelly J delivered the judgment of the Court, in which Murray CJ and Geoghegan, Macken and Finnegan JJ concurred, and its effect is that two Irish Times journalists could decline to answer questions about their sources (unsurprisingly, there is a lot of coverage in that paper: see here, here, here, here and here).

As I wrote in my previous post, the Supreme Court in Mahon Tribunal v Keena [2009] IESC 64 (31 July 2009) (also here (pdf)) allowed the appeal against the decision of the High Court in Mahon v Keena [2007] IEHC 348 (23 October 2007). Fennelly J delivered the judgment of the Court, in which Murray CJ and Geoghegan, Macken and Finnegan JJ concurred, and its effect is that two Irish Times journalists could decline to answer questions about their sources (unsurprisingly, there is a lot of coverage in that paper: see here, here, here, here and here).

1. Introduction

There are at least three important aspects to Fennelly J’s decision. The first relates to his almost exclusive reliance on the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR), rather than the Irish Constitution. The second relates to his approach to the issues in general and to his treatment of the High Court judgment in particular: in short, he felt that the High Court had overstated the balance against the appellants. And the third relates to what he had to say about the nature of a journalist source privilege: in short, he preferred to avoid such language in favour simply of a balancing test.…

Supreme Court allows journalists’ appeal

The Supreme Court has held that two Irish Times journalists can assert a privilege to refuse to answer questions about their sources, reversing the High Court decision in Mahon v Keena [2007] IEHC 348 (23 October 2007). From the Irish Times breaking news website:

The Supreme Court has held that two Irish Times journalists can assert a privilege to refuse to answer questions about their sources, reversing the High Court decision in Mahon v Keena [2007] IEHC 348 (23 October 2007). From the Irish Times breaking news website:

Court upholds Mahon appeal

The Supreme Court has upheld an appeal by Irish Times editor Geraldine Kennedy and public affairs correspondent Colm Keena against a court order requiring them to answer questions from the Mahon tribunal about the source of an article about former taoiseach Bertie Ahern. …

Revised: The decision is also noted by Cian on Blurred Keys and is now avaialble as Mahon Tribunal v Keena [2009] IESC 64 (31 July 2009); it is also here (pdf) on the Irish Times website.

See also the Belfast decision in the case of Suzanne Breen and a decision of the Supreme Court of Western Australia earlier this week, both reaching similar conclusions.…

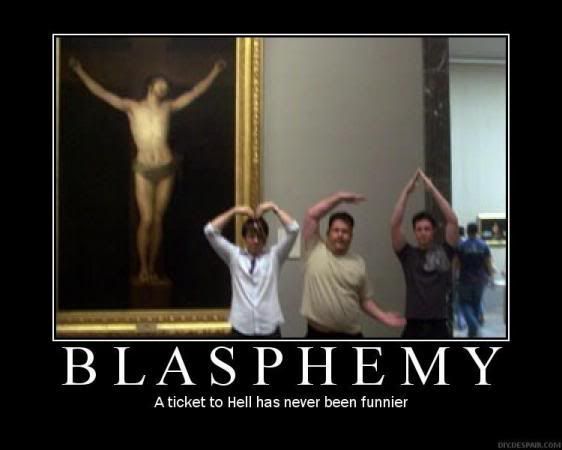

Blasphemy: Pluralisation and Content

In The Godfather, Part III, Michael Corleone (played by Al Pacino) laments

Just when I thought I was out… they pull me back in.

I know how he feels (though without the mafia connections, obviously). I had intended yesterday’s post to be my last on blasphemy for some time, but then Eoin Daly, a PhD student in UCC, went and spoiled it all by writing an excellent guest post on CCJHR blog about the new offence; update and Michael Walsh, a law student at NUI Galway, has written a compelling post critiquing some of my earlier analysis on the issue. To being, some extracts from Eoin’s post:

…The Pluralisation of Blasphemy law: Possible Constitutional Implications

… the most interesting aspect of the new offence [is] the fact that is has been “pluralised”, encompassing material that is “grossly abusive or insulting in relation to matters held sacred by any religion.” … blasphemy law has shifted from a religious to a secular legitimation, from the protection of a particular religious truth, to the protection of the sentiments of religious persons, of all recognised affiliations.

However, it is this very fact of a secular legitimation, of “outrage among a substantial number of [any religion’s] adherents”, which renders the contours of the offence unfeasibly vague.

How will the blasphemy offence work?

It’s a pity that Part 5 of the Defamation Act, 2009, relating to blasphemy, has dominated the coverage of the Act at home and abroad (eg, US, Denmark (pdf)), since the legislation does considerably more than that. It is radical modernisation of Ireland’s defamation laws, and is a vast improvement on what had gone before. In particular, it provides several means to ensure much speedier resolution of defamation cases; it provides for a new defence of reasonable publication; it significantly improves the law relating to damages in defamation cases; and it gives a stable statutory footing to the Press Council. These will be matters to which I will return on this blog; but, before that, I want to make another comment about Part 5 of the Act.

It’s a pity that Part 5 of the Defamation Act, 2009, relating to blasphemy, has dominated the coverage of the Act at home and abroad (eg, US, Denmark (pdf)), since the legislation does considerably more than that. It is radical modernisation of Ireland’s defamation laws, and is a vast improvement on what had gone before. In particular, it provides several means to ensure much speedier resolution of defamation cases; it provides for a new defence of reasonable publication; it significantly improves the law relating to damages in defamation cases; and it gives a stable statutory footing to the Press Council. These will be matters to which I will return on this blog; but, before that, I want to make another comment about Part 5 of the Act.

Part 5 of the Act consists of three sections. Section 35 abolishes the common law offences of defamatory libel, seditious libel and obscene libel are abolished. Section 36, subsections (1)-(2) create the new crime of blapshemy, by making it an offence to cause outrage among a substantial number of the adherents of a religion by intentionally publishing material that grossly abuses or insults matters held sacred by their religion. This is narrowed in two ways: subsection (3) provides a saver for publications of genuine literary, artistic, political, scientific, or academic value; and subsection (4) excludes from the definition of “religion” an organisation which principally aims to make a profit or which employs oppressive psychological manipulation.…

Monkeys and blasphemy

On the monkeys-and-typewriters principle, I suppose it was inevitable that Kevin Myers would eventually write something with which I would agree. He did, today, in the Irish Independent:

On the monkeys-and-typewriters principle, I suppose it was inevitable that Kevin Myers would eventually write something with which I would agree. He did, today, in the Irish Independent:

I have the right not merely to offend people, but to intend to

… The Ahern law on blasphemy must be the first law ever whose instigator is desperately hoping that it will never be invoked. Its potency depends not upon any legal definition on what blasphemy actually consists of, but solely on the “outrage” that the remark in question might intentionally cause.

… Well, frankly, I think I have the right not merely to offend people, but the right to intend to do so. It is up to them, and their personal capacity to control their emotions, as to whether or not they are outraged. …

Polemical as always, and trenchant, he is making much the same point as I essayed here and here.

On the same principle, it was probably just as inevitable that I would at some stage feel a little sorry for Gerry Ryan. I did, today, when I learned that he had been the subject of a complaint to the Broadcasting Complaints Commission for wondering whether it would be considered blasphemous if someone said on air that “God is a bollocks”.…

Typography for Lawyers

I love this website: Typography for Lawyers. Typography is the visual component of the written word, and even though the legal profession depends heavily on writing, legal typography is often poor. So, Matthew Butterick has started that site as a guide to typography for lawyers – in his view, good typography makes written documents more professional and more persuasive. He gives a wonderful example of where bad typography led to serious problems (I won’t spoil the effect, click through to find out for yourself); and he gives very sage advice about using the Times font (advice which I only occasionally take, but then, do as he says, not as I do!). This is a wonderful website. Go, read, learn, enjoy.…

I love this website: Typography for Lawyers. Typography is the visual component of the written word, and even though the legal profession depends heavily on writing, legal typography is often poor. So, Matthew Butterick has started that site as a guide to typography for lawyers – in his view, good typography makes written documents more professional and more persuasive. He gives a wonderful example of where bad typography led to serious problems (I won’t spoil the effect, click through to find out for yourself); and he gives very sage advice about using the Times font (advice which I only occasionally take, but then, do as he says, not as I do!). This is a wonderful website. Go, read, learn, enjoy.…

© cearta.ie 2024. Powered by WordPress